Introduction: The Economics of Transformative AI

I. The Context for the Volume

AI capabilities have been relentlessly improving across a variety of benchmarks. And in November 2022, a new chapter in this story began. ChatGPT became the fastest-growing consumer app of all time. Soon after, a wave of similar AI systems – Claude, Gemini, and Grok – followed, each built in a similar spirit with rapidly improving capabilities. Understandably, a surge of interest – both excitement and alarm – has accompanied this ongoing surge of technological progress.

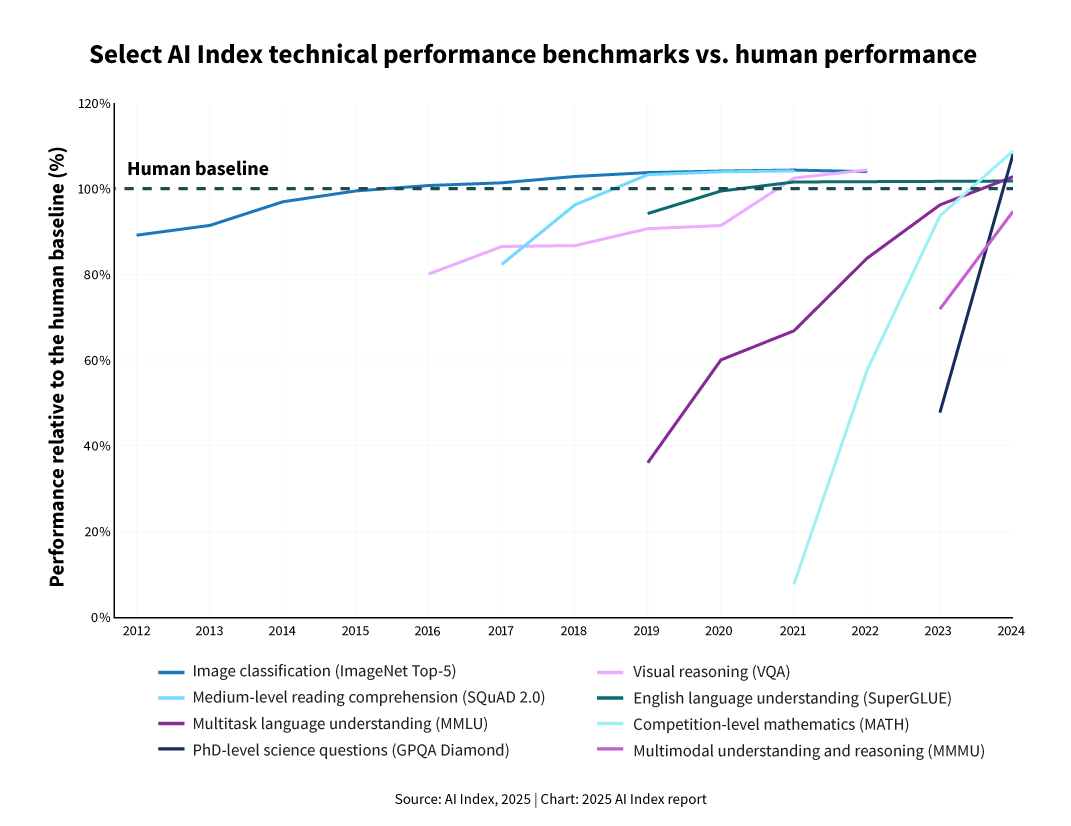

Figure 1 provides a snapshot of the technical developments since 2012: AI systems have approached, and then exceeded, human-level performance in a growing set of demanding tasks, from competition-level mathematics to scientific reasoning. In truth, though, any single chart will struggle to adequately capture the current pace of progress. Measuring the change taking place is becoming increasingly difficult: “Rapidly advancing technology,” reported the Financial Times at the end of 2024, “is surpassing current methods of evaluating and comparing large language models.”1 A race is underway not only to build ever more powerful AI systems, but also to design reliable benchmarks with which to monitor that progress.

Figure 1: AI technical performance since 2012.2

Where, though, is this progress taking us? Throughout 2025, the leaders of the largest AI companies set out their predictions for what lies ahead. All of them described a similarly remarkable trajectory for AI – though each in a slightly different way.

“We are now confident,” said the co-founder of OpenAI, Sam Altman, that “we know how to build AGI as we have traditionally understood it.”3

“A system that’s capable of exhibiting all the cognitive capabilities humans can,” predicted the co-founder of DeepMind, Demis Hassabis, is “probably three to five years away.”4

“Powerful AI,” remarked Dario Amodei, the founder of Anthropic, using his preferred term for a similarly capable technology, was “two to three years” away.5

Others in the field have made predictions in a similar spirit. However likely you believe these scenarios are to unfold, they are now conceivable in a way that was hard to believe only a few years ago.

Driving this remarkable progress in the power of AI systems, and underwriting these confident claims from the leaders of the frontier AI companies about their future capabilities, are remarkable levels of investment. In 2024, global private investment in AI hit a record high, reaching $150.79 billion.6 The US is responsible for the majority of this surge, with levels of private AI investment ($109.1 billion) that are almost 12 times higher than China ($9.3 billion) and 24 times higher than the UK ($4.5 billion).

How large exactly is this scale of investment? In truth, there are very few individual technical challenges—if any—at which so much financial resource has been directed. The Apollo Project to put man on the moon in the 1960s, for instance, which ran for more than a decade, cost around $25 billion in 1973 dollars, about $180 billion today—not dissimilar in scale from a single year of US private investment in AI.7 The Manhattan Project to build the nuclear bomb in the 1940s cost around $2 billion in 1945 dollars, about $11.6 billion today—barely a tenth of what US companies invest in AI each year.

And yet, despite all this—the remarkable achievements in AI to date, the striking predictions of what lies ahead for the field, the enormous financial investment fueling all this activity—comparatively little attention is currently invested in understanding the economic consequences of what is being built. What’s more, when debates and discussions about these possible futures do take place, they tend to unfold within communities of like-minded people, protected from one another by traditional organizational silos and well-established disciplines.

Given the current capabilities of AI, this lack of shared attention is unfortunate. But given what might be possible for the technology in the future, it is a more serious shortcoming. Starting to close this gap—between the resources invested in developing AI, and the attention invested in understanding AI—is one of the most important tasks of the moment. That is the central purpose of this second volume of The Digitalist Papers.

II. The Purpose of the Volume

It may be helpful to recall the broader purpose of The Digitalist Papers project. Inspired by the spirit of The Federalist Papers—a forum for debating the architecture of a new political order—this series brings together leading thinkers to examine how artificial intelligence may reshape our economies, institutions, and societies. Volume 1 explored the implications of AI for democracy; this second volume turns to its economic dimensions, focusing on how transformative AI might alter production, work, and prosperity itself. It brings together leading economists, technologists, philosophers, and others to explore the key economic challenges and opportunities of “transformative AI,” or TAI. Most significantly, though, it is also focused on how we might respond to whatever lies ahead.

In what follows, we define “TAI” as advanced AI systems that will usher in an economic transformation comparable to the industrial revolution, but on a much shorter timescale. They exhibit intelligence surpassing the most capable humans across multiple fields, capable of performing not only routine cognitive work, but also complex tasks like solving mathematical theorems, creating novel works, or directing experiments autonomously.

This is not, then, a volume about the current state of AI and its implications, but TAI and what it would mean. With that in mind, all contributors in this volume have been asked to take the premise that the TAI will arrive in the not too distant future, rather than debate its feasibility or timelines. Others can and should do that. Our ambition is instead to stay ahead of a fast-moving technology and to focus on the economic implications of the scenario where TAI is achieved.

As we shall see in the contributions that follow, TAI would be deeply disruptive to how we live and work together in society. Its effects are likely to unfold in a variety of different ways, for good and for bad: It might, for instance, dramatically boost productivity and scientific progress, but at the same time it might also disrupt labor markets and radically change the distribution of wealth and power.

And so, with that scale of disruption in mind, we also asked all contributors in the volume to not only focus on better understanding the consequences of TAI but also reflect on how we ought to respond to its effects. What changes are needed to our institutions, norms, or policy frameworks to make sure that all of us can flourish in a world with TAI? That practical dimension is important, and a focus of what follows, too.

In short, this volume of The Digitalist Papers has two central purposes: to take the idea of TAI seriously and consider its consequences, and to begin to set out how we respond.

The volume is divided into two parts. To open the volume, a set of short, visionary essays, authored by leading figures at the technological frontier, set out sketches of different scenarios for the future. Each of these provides us with a glimpse of what TAI might mean for the economy and society. Then, a set of longer essays explores the consequences of TAI in more detail and how we might respond.

This volume of The Digitalist Papers is not intended to be comprehensive in its coverage. Contributors were free to choose the areas they focused on. Many important themes are included, but others are not. Equally, this volume is not intended to be a unified manifesto for action. In the pages that follow, many policies are proposed. Some of these are complementary, but often they clash. This is inevitable, given the variety of views and disciplines we have drawn upon. Indeed, it is also desirable. We see this volume of The Digitalist Papers as the start of a conversation, a collection of diverse voices exploring one of the great challenges of our time, not a definitive plan of action.

III. An Outline of the Volume

The volume begins with a set of “vision essays” from the world’s leading technologists. These are people—Eric Schmidt, Sarah Friar, Daniela Rus, and Steve Jurvetson—who, in different ways, are all involved with building the technology of the future. Each of these set out compelling AI scenarios that illustrate potential technological trajectories, disruptions, or opportunities created by powerful AI systems. They aren’t predictions but provocations, visions of what matter, setting the intellectual tone and imaginative scope for the essays that follow.

Then, in the opening essay of the next section, Yoshua Bengio sets the scene. TAI has the potential to benefit all of us, he argues, but it also presents us with a variety of serious risks that spill over boundaries between countries. In this essay, he gathers these risks together—if we are to flourish in the future, he explains, we must begin by recognizing their global nature and the need for an international response.

One of the most significant and widely commented-upon disruptions that TAI might bring about is to the world of work. These new technologies might make us more collectively prosperous than ever before—but how do we share that prosperity if our traditional way of doing so, paying people for the work they do, is less effective than in the past? In this volume, various authors explore this challenge and how we ought to respond, in a variety of ways.

An immediate question is how to prepare the next generation of workers for a future labor market that might look very different from the past. To that end, Avital Balwit draws on her experience at a frontier AI company, Anthropic, and as a TAI researcher, to provide practical career advice to those thinking about the future of work. Our traditional approach, refined through the 20th century, of preparing young people with the right skills is not sufficient to the scale of the challenge ahead, she argues, and instead proposes a focus on developing new mindsets.

Building on this practical perspective, David Autor and Neil Thompson set out a new framework for understanding how TAI is likely to reshape the structure of work. TAI will not simply eliminate jobs; it will reshape the value of human expertise. And confronted, again, by great uncertainty, unsure which occupations will thrive or struggle, they argue we can use this framework for thinking about very different scenarios, from gradual automation to complete human labor obsolescence—and how we can prepare for them.

But suppose a world with TAI is closer to that latter scenario, and labor markets fail to provide enough well-paid work for everyone to do—full stop. How do we share prosperity in that society?

In recent years, there has been growing interest in interventions that would take on this distributional task—from a basic income, which would provide everyone with some form of payment irrespective of their status in the labor market, to a job guarantee scheme, which would provide work to those who want it. Nicolas Berggruen and Nathan Gardels explore a new possibility: universal basic capital, where all individuals are given an ownership stake in TAI. And in turn, Ioana Marinescu sets out a safety net that is able to respond to the fact that the scale of labor market disruption might change over time, a flexible set of interventions that can adapt dramatically in response to the magnitude of the challenge.

How to finance interventions on this scale? That is the focus of the essay by Anton Korinek and Lee Lockwood. Preserving fiscal stability in the age of TAI, they argue, is important not only if we are to respond effectively to labor displacement, but also to ensure that the state is able to fund the many other dimensions of its role—from military capabilities to infrastructure investments—that might affect a country’s global position. A country’s prosperity in a world with TAI would depend, in part, on whether it is able to rise to meet these fiscal challenges.

But it is important to remember that if TAI does devalue or displace human work, the challenges are not simply economic. The essay by Betsey Stevenson reminds us that, if societal well-being is to rise in that world, we also have to focus on non-economic problems: not simply how to share valuable resources so that everyone is able to benefit from the extraordinary productive capacity of these new technologies, but how to provide people with meaning and purpose in a transformed working world, and how to maintain trust and social cohesion in a society that looks very different from the past.

The economic impact of TAI, though, is not limited to the world of work alone. The essay by Ajay Agrawal and Joshua S. Gans explores the macroeconomic effect of this powerful technology. It is revealing, they argue, to think of TAI as a “genius supply shock” to the economy—a sudden influx of abundant, cheap, and fast agents that can outperform human beings in many areas of their lives. It is hard for companies to know how to respond to that sort of shock, such a technological discontinuity from what has come before. And they argue that two policies in particular, regulatory sandboxes and regulatory holidays, could help business leaders learn how to make effective use of these tools.

The essay by Joseph E. Stiglitz and Màxim Ventura-Bolet explores a further macroeconomic effect of TAI—how it is likely to shape the production and distribution of “good” information throughout society. Their diagnosis is that, in a world with TAI, we would face three distinct problems: an undersupply of good information, an oversupply of mis- and disinformation, and an undersupply of efforts to correct the latter. And the authors describe the legal and regulatory framework that might solve these problems. Then, the essay by Alex Pentland and Alexander Lipton focuses on the underpinnings of economic life: the financial system. It is not enough, they argue, to focus on traditional production, which is where we tend to direct our time and attention; we also need to consider the disruptive impact of TAI on trade and investment.

TAI is likely to be highly disruptive, but its consequences are also highly uncertain. In part, that is because the future depends on choices that we make today. The essay by Ramin Toloui explores how the same technology can have very different impacts on society, depending on who controls it, how it is deployed, and how governments respond. He introduces a novel framework for organizing different types of technological revolution, a tool that allows us to distinguish between different scenarios for TAI—those we might choose and, importantly, others we might avoid. The essay by Gabriel Unger re-emphasizes this uncertainty. The economic consequences of TAI are not set in stone, they both argue, but will be shaped by the decisions that we take today, and they draw attention to the gap that motivates this volume of The Digitalist Papers—the mismatch between how large the stakes are, for good and for bad, and how limited the conversation about TAI is at the moment.

A common concern about TAI is that it would lead to a far greater concentration of political and economic power among a small number of companies and individuals who are responsible for developing these technologies. The fear is that, despite the great promise of such a power technology, ordinary people may nevertheless be left worse off. In their essay, Susan Athey and Fiona Scott Morton explore this problem: The promise of TAI is that the productivity gains of this powerful new technology are passed on to consumers—as lower prices, perhaps, or better products—but outcomes where consumers are left better off are far from inevitable. They set out a spread of policy ideas that could help make sure the benefits of TAI are widely shared.

One of the challenges of TAI, which runs through several of the essays in this volume, is that it shows little respect for the boundaries between countries. The technology flows across borders, with consequences that spill around the world. Anna Yelizarova puts the labor market challenge we highlighted earlier in the global context. She sets out a proposal for a global mechanism that is capable of sharing out prosperity across borders, a “global dividend” that provides recurring payments to everyone—a difficult proposal to implement, as the author explains, but one with intriguing precedents. Nick Bostrom explores the challenge of international governance more generally. His answer is, somewhat surprisingly, a more radical version of what we already have—an “open global investment” approach, where private AI companies, operating within government-defined frameworks, are open to international shareholding. This, he explains, is to be preferred over frequently proposed alternatives, such as a CERN or Manhattan Project for AI.

Today, the pursuit of powerful AI systems is defined by the geopolitical interaction between China and the US. And so, the nature of the interaction between these two countries is likely to shape how TAI unfolds. Lisa Abraham, Joshua Kavner, Alvin Moon, and Jason Matheny use game theory to model this race and to draw practical insights on how this interaction could be turned from one of competition to one of greater cooperation. With this essay, the authors are following in a rich intellectual tradition: Their home institution, RAND, developed many of the most important game theoretic tools for thinking about the technological race that defined the previous century: the pursuit of nuclear weapons. Alvin W. Graylin shares the same aspiration, calling for the US and China to go “beyond rivalry” and setting out a spread of interventions to bring that about.

Once again, this volume of The Digitalist Papers is not intended to be comprehensive. But we hope that, in bringing together this group of remarkable thinkers, we can better understand the challenges and opportunities of TAI—and start to make sense, together, of how we ought to respond.

-The Editors

Daniel Susskind, Erik Brynjolfsson,

Anton Korinek, Alex Pentland, Ajay Agrawal

1. Cristina Criddle, “AI Groups Rush to Redesign Model Testing and Create New Benchmarks,” Financial Times, November 9, 2024, https://www.ft.com/content/866ad6e9-f8fe-451f-9b00-cb9f638c7c59.

2. Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2025 (Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI, 2025), https://hai.stanford.edu/ai-index/2025-ai-index-report.

3. Sam Altman, “Reflections,” Sam Altman (blog), January 5, 2025, https://blog.samaltman.com/reflections.

4. Alex Kantrowitz, “Google DeepMind CEO Demis Hassabis: The Path to AGI, LLM Creativity, and Google Smart Glasses,” Medium, January 26, 2025, https://kantrowitz.medium.com/google-deepmind-ceo-demis-hassabis-the-path-to-agi-llm-creativity-and-google-smart-glasses-d09ddcd471a2.

5. Dario Amodei, interview with CNBC “Squawk Box,” CNBCTV, YouTube, January 21, 2025, https://youtu.be/7LNyUbii0zw.

6. Njenga Kariuki, “Chapter 4: Economy,” in Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2025 (Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI, 2025), https://hai.stanford.edu/ai-index/2025-ai-index-report/economy.

7. “How Much Did the Apollo Program Cost?,” The Planetary Society, accessed November 20, 2025, https://www.planetary.org/space-policy/cost-of-apollo.