Beyond Rivalry: A US-China Policy Framework for the Age of Transformative AI

Many observers fear that the pursuit of transformative AI or artificial general intelligence (AGI)1 presents a challenge to the existing global order. Their worry is that the US and China, the two global leaders in AI, are now locked in a destructive race to build the most capable version of the technology, which could lead to unintended consequences and global instability.

But in this essay, the author explores an alternative path for the US and China, one where these countries go “beyond rivalry,” and sets out how this more hopeful, cooperative outcome might be achieved.2

I. Introduction: From Competition to Cooperation

The arrival of AGI will reorder power, wealth, and security; whether it stabilizes or shatters the global system depends on what the United States and China do next. As the world’s AI leaders, the US and China face a critical choice: whether to continue down a path of rivalry and arms-race thinking, or to embrace an agenda of cooperation and shared stewardship. This essay argues for the latter. By focusing on US domestic readiness and global partnership, we can move beyond a zero-sum mindset toward a multilateral approach that manages the risks of AGI while spreading its gains.

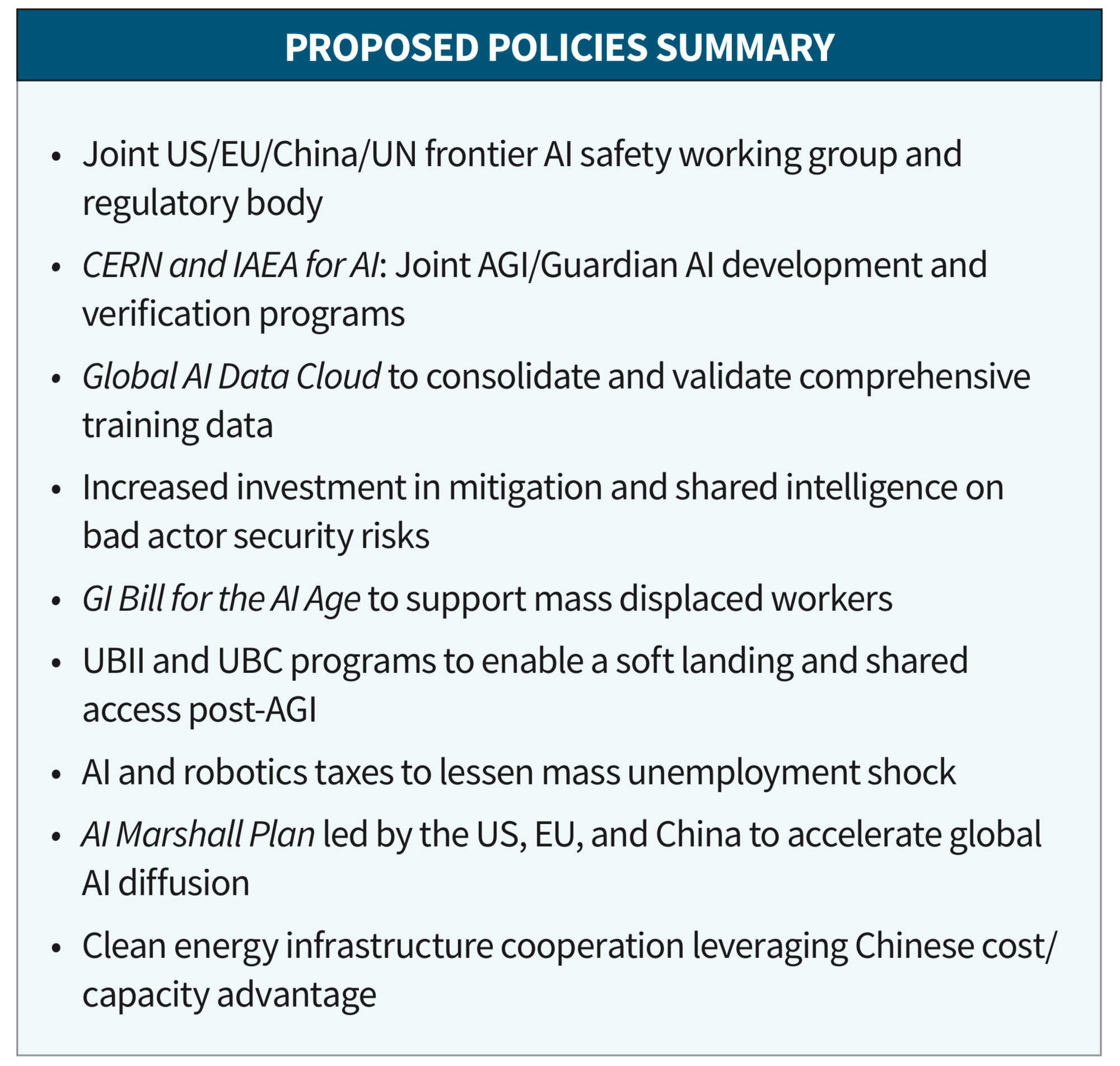

Just as the post-WWII order was defined by visionary US initiatives like the Marshall Plan and multiple international institutions, the AGI era calls for American leadership that transcends competition and forges new norms of trust. The goal is to ensure that AGI evolves as a public good for all humanity, not a source or accelerant of conflict. While the White House’s “America’s AI Action Plan,”3 released in July 2025, discusses some important points in accelerating innovation, it lacks the holistic perspective needed to ensure a smooth deployment to the economy and avoid heightening geopolitical tensions. This paper offers a new framework of cooperation on global alignment, shared safety standards, inclusive economic policies, and proposes a pragmatic path to reduced risk while expanding shared gains.

“Just as the post-WWII order was defined by visionary US initiatives like the Marshall Plan and multiple international institutions, the AGI era calls for American leadership that transcends competition and forges new norms of trust.”

The paper moves through several important steps: (1) define AI categories with policy-relevant distinctions; (2) explain why there is no “AGI finish line”; (3) decompose risk and show that misuse dominates misalignment today; (4) argue cooperation and openness are prerequisites for safe AGI; (5) set US domestic readiness actions such as UBII, reskilling, or open access; (6) explain why globally representative data is essential; and (7) propose a dual-track architecture of cooperation on safety and the public good, and responsible competition elsewhere.

Ultimately, “Beyond Rivalry” is a call to action for policymakers and industry leaders to approach the age of AGI not as a winner-take-all, great-power contest, but as a chance to design a new global alignment and pursue shared security, shared prosperity, and shared wisdom in guiding this powerful technology.

II. Defining AI

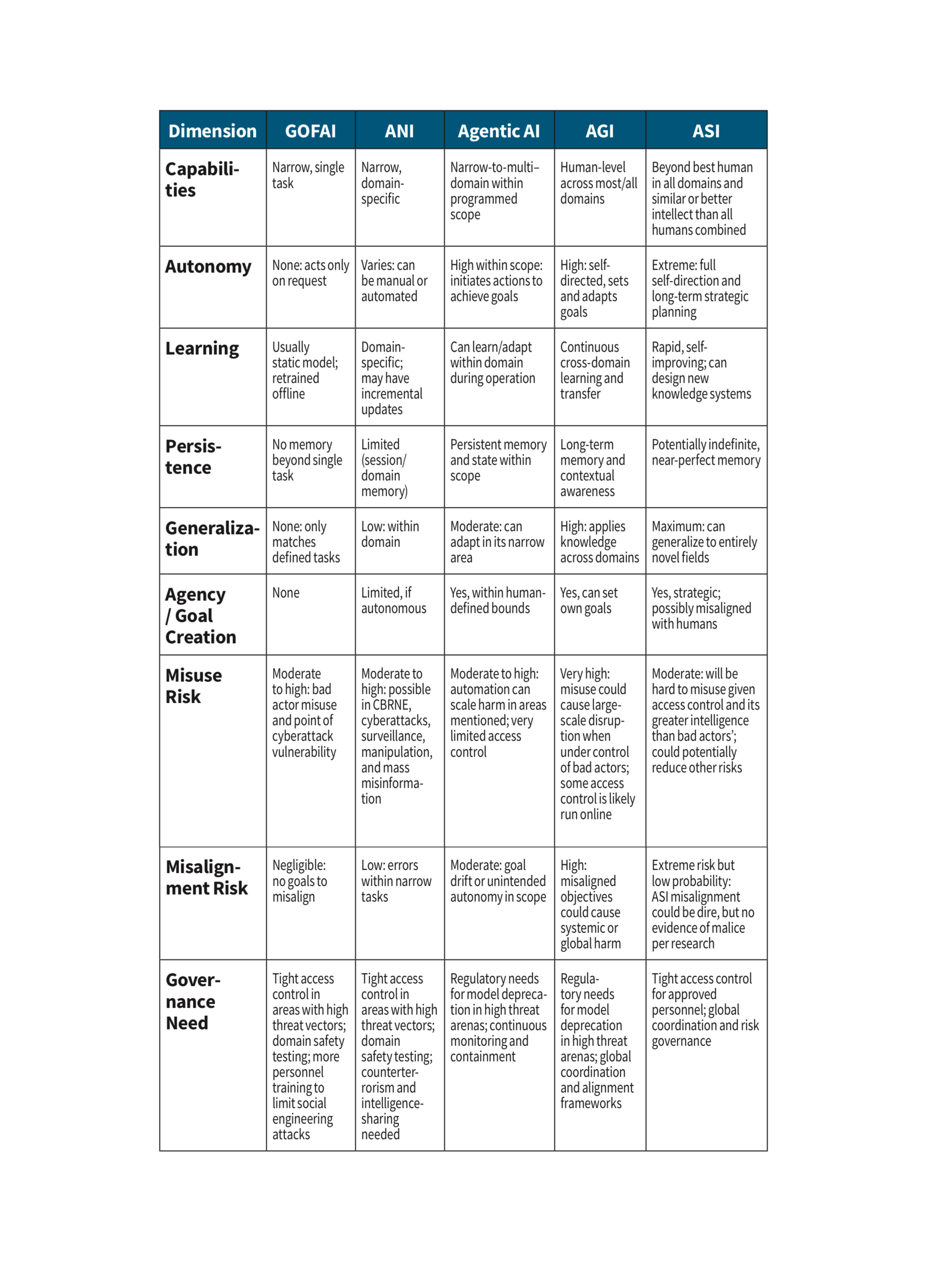

A first step toward sensible policy is understanding what we mean by the different types of AI:

• GOFAI (Good Old-Fashioned AI)

• ANI (Artificial Narrow Intelligence)

• Agentic AI

• AGI (Artificial General Intelligence)

• ASI (Artificial Superintelligence)

GOFAI, also known as symbolic AI, is the early form of AI, where rules are explicitly described by the programmer. ANI represents most of the recent AI we see in the world today, where the systems are designed to help perform a specific task or function. They can respond to direct human input (e.g., chess engine, translation system, or most generative AI) or be given some level of agency for self-directed capabilities (e.g., autonomous driving, coding agent, or shopping bots). A subset of ANI without agentic capabilities is called Tool AI.

“A successful implementation of AGI would mean that eventually, most cognitive labor could be replaced by machines. And when integrated with robotic systems and tool use, most manual human labor could also be displaced.”

AGI usually refers to AI systems with humanequivalent cognitive abilities across a wide range of tasks—essentially, software that can learn or reason its way to solve novel problems and self-improve roughly as a human would. A successful implementation of AGI would mean that eventually, most cognitive labor could be replaced by machines. And when integrated with robotic systems and tool use, most manual human labor could also be displaced. This would lead to a complete restructuring of the global economy and our way of life. In the last couple of years, the concept of Agentic AI has risen in public awareness, which denotes the ability of AI systems to have a greater level of autonomy in completing complex tasks by responding to issues directly, and working in groups or using tools when necessary. Both ANI and AGI systems can possess agentic capabilities, but it’s not a requirement and doesn’t necessarily imply innate intent or self-directed agency. (There is much debate over the eventuality of AI and consciousness, but given the lack of scientific agreement on human and animal consciousness, this paper will not include further discussion on this topic.)

ASI, on the other hand, denotes intelligence far surpassing human level, capable of recursive self-improvement and reaching a point where it may become incomprehensible or uncontrollable by humans. Importantly, AGI does not automatically imply ASI. Many experts believe we may achieve AGI (some optimistic forecasts say within this decade), but ASI—a system “more intelligent than all of humanity combined”4—remains speculative and would introduce qualitatively new risks and benefits. This paper will primarily deal with AGI-level issues and below, but ASI alignment is discussed, and the suggested policy recommendations can apply to ASI concerns as well. (More details on different types of AI can be found in Appendix A.)

III. There is No AI Finish Line

AI policy discourse often assumes that whichever nation or company first reaches AGI—the “finish line”—will gain a permanent, decisive strategic advantage (DSA): a monopoly on future innovation or global influence. Clarifying the lack of an actual finish line for AI tempers both hype and fear. Although achieving AGI would be momentous, it would not instantly confer godlike omnipotence to its owner. This notion has been stoked by comments like Russian President Vladimir Putin’s oft-quoted warning that “the one who becomes the leader in [AI] will be the ruler of the world.”5 But reality is far more complex, and less zero-sum.

“Clarifying the lack of an actual finish line for AI tempers both hype and fear. Although achieving AGI would be momentous, it would not instantly confer godlike omnipotence to its owner.”

History shows that lead times in transformative technologies can be fleeting. The US held a nuclear weapons monopoly for only four years before the Soviet Union caught up. In the internet era, barriers to knowledge diffusion are even lower. Advances in AI tend to cross borders rapidly via publications, open-source code, and talent flows.

A recent analysis in the MIT Technology Review clearly describes all the reasons why “there can be no winners in a US–China AI Arms Race.”6 In truth, any initial advantage from achieving AGI first could be short-lived—especially if pursued in secret or isolation. New frontier models from Chinese labs like DeepSeek, Alibaba, and Minimax clearly show that the big lead US labs once enjoyed has significantly narrowed.7,8 Competing labs, especially with the quality of new open-source models, would quickly replicate breakthroughs (as we’ve seen with large language models), and an antagonistic stance would only motivate others to redouble their efforts. Conversely, a cooperative approach—sharing safety research and setting joint standards—could allow many nations to benefit and learn in parallel, reducing incentives for reckless acceleration.

Crucially, even a successful AGI “win” by one side does not guarantee lasting security or advantage. An AGI is not a static superweapon; it’s more akin to a living ecosystem of software that others can also build on, improve, or weaponize. If the US “pulls ahead” and treats AGI as a tool of dominance, it could trigger a dangerous proliferation of AI as other major powers race to develop their own (perhaps in less controlled ways). The long-term outcome would likely be greater instability, not less. Nonproliferation arrangements analogous to the Cold War period could not be enforced with this technology. That is why leading AI researchers like Yoshua Bengio stress that the global nature of AI technology “requires international cooperation. Just as nuclear weapons were subject to international treaties to prevent misuse, AI should be governed by global safety standards.”9 In short, there is no single finish line that allows one nation to lock in supremacy; there is only a continuous process of advancement that will involve many actors. The real question is whether those actors will operate in competition or coordination.

“Instead of chasing a possibly pyrrhic victory—e.g., trying to be first at all costs—the US should aim to shape the playing field, setting rules that encourage safety, ethics, and shared benefit.”

The push by US labs and administration for escalating the AI race has been driven by the false belief that we are far ahead of other nations and that with stronger sanctions and diffusion controls, our lead can become permanent. This belief rests largely on the perceived control we have over the supply of Nvidia graphics processing units (GPUs) used in AI training. Unfortunately, this once key advantage of GPU supply is no longer so important: Recent trends show AI scaling from new “descaling” factors that don’t rely solely on access to the most advanced GPUs (algorithms, techniques, inference, tools, etc.) can now deliver linear or exponential improvements to the quality of model outputs versus traditional raw scaling factors (model size, training data, training compute) that can only deliver logarithmic gains (see Figure 1). We have no moat, and neither does China. Policymakers should resist the simplistic narrative of a winner-takes-all “AGI arms race.” Instead of chasing a possibly pyrrhic victory—e.g., trying to be first at all costs—the US should aim to shape the playing field, setting rules that encourage safety, ethics, and shared benefit.

Figure 1: Traditional scaling factors are now less impactful as new improvement factors appear, reducing over-dependency on brute force scaling of model size and compute resources.10

IV. AI Risks: Misuse Is Greater than Misalignment

There are many in the AI safety community who view ASI as an existential threat to humanity: They believe we will inevitably lose control, and AI will either intentionally or accidentally turn all humans (all life) into “paper clips”11 or “computronium.”12 This is often categorized as alignment risk. Most of these concerns are based on complex series of thought experiments where we anthropomorphize AI and hypothesize how a self-serving, hyperintelligent being could behave. But there has been no clear research showing that AI becomes more evil or aggressive toward humans when they get smarter. In fact, recent research from the Center for AI Safety points to the conclusion that the more data AI models are trained on, the more they will identify emerging utility value and try to optimize global utility for the whole system.13 This is very encouraging, given that advanced AI models will have trained on most of the available information we have and would try to maximize the benefit of the known world. It could be argued that they could play a positive role in helping us solve long-lived conflicts and resolve global challenges like climate, hunger, disease, etc. The other way to interpret the findings is that if we don’t cooperate and share training data globally, the resulting AGI could be biased toward a specific goal or subgroup and become dangerous weapons in the wrong hands.

“The other way to interpret the findings is that if we don’t cooperate and share training data globally, the resulting AGI could be biased toward a specific goal or subgroup and become dangerous weapons in the wrong hands.”

In recent discussions of AI’s existential threat, some experts have used the concept of P(doom)—the probability of an AI-induced doom for humanity. P(doom) is an umbrella term often used to denote one’s perception of AI’s existential risk (e.g., 10% = one in ten chance of a catastrophic AI outcome). Unfortunately, the term represents a highly subjective number that isn’t consistently defined or clearly derived. Some use it to mean the chance that AI kills all humans, others that AI subjugates humans, and some even include oligarchs using AI to rule humans. And there is no clear time frame, ranging from the next 10 years to the end of time. It would be helpful to interject some rigor in defining the various types of AI-related risks so we can have a more objective way to evaluate and compare them, and use that to guide a sensible policymaking process and prioritize resources. (More details on the associated risk factors for the different types of AI can be found in Appendix A.) The four major types of AI risks I see are:

• AGI misalignment: Resulting in human destruction or subjugation by AI

• Bad actor misuse: Rogue groups or entities use AI to harm or manipulate the population

• Societal misuse: Mass job displacement, power concentration, or civilization collapse

• Government misuse: Unfettered geopolitical conflict escalation leading to global war

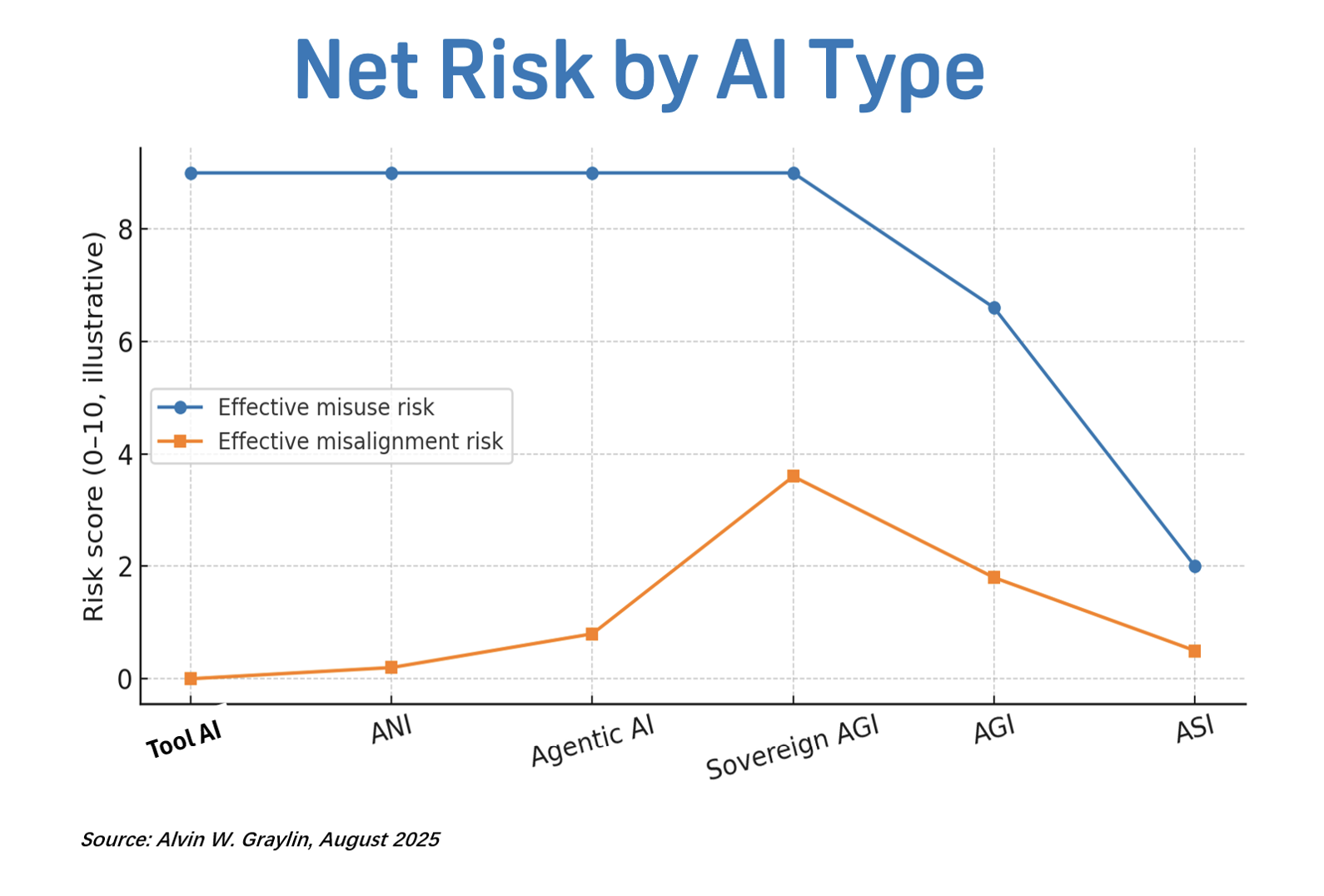

All four could lead to some form of “doom,” but with differing levels of severity and likelihood (see Figure 2). For simplicity, we can effectively consolidate the four risks into two groups: (1) AI misalignment risks and (2) misuse risks by humans.

Figure 2: AI risk type likelihood vs. severity.

The net risk of each group can be obtained by multiplying the likelihood with their severity (see additional data in Appendix B). Most AI safety efforts to date are focused on alignment-related issues, but when evaluating the risks objectively, clearly human misuse poses a far greater net risk to the world. And more interestingly, sovereign AI—AI dominated by one country, which is the path the US and many Western nations are prioritizing—may be the most high-risk option: It has all the downside of high misuse risk and higher misalignment risks because it is trained on incomplete datasets and biased goals. If we can agree that reducing net risk is a common goal, then we can build smarter and safer models by consolidating our constrained development and training resources with a globally integrated dataset and value systems that represent all cultures.

It is imperative we do this, because the dangers of misuse are clear and present. While superintelligence scenarios garner headlines, many experts, concurring with the argument above, believe the more urgent threat in the coming decade is not a conscious AI deciding to harm humanity, but humans using AI to harm each other. Geoffrey Hinton, a pioneer of deep learning often dubbed the “Godfather of AI,” recently sounded the alarm about bad actors exploiting AI tools. Hinton notes that even the relatively advanced AIs we have now (or will have soon) could be misused to create new weapons, conduct cyberattacks, generate biological agents, or empower authoritarian surveillance and propaganda at unprecedented scale.14 Indeed, a recent International AI Safety report compiled by 100 global experts underscores the near-term misuse scenarios.15 It catalogue show AI could facilitate everything from automated cyberattacks on financial grids to AI-designed bioweapons, disinformation, and cyber sabotage as key examples. In one striking data point, the report notes that AI-generated misinformation and deepfakes are rising rapidly worldwide, and that even mid-tier AI tools can assist in orchestrating destabilizing influence campaigns. No country is truly safe from these dangers.

Guardian over Slaves

“Our collective goal should be GAI, rather than just AGI. AI alignment should not mean just raw obedience; it must possess deep human understanding and a sense of benevolence.”

However, if the world can pool our limited resources to find a way to better align AGI (and later ASI) to prosocial values, we have an opportunity to create what I would call a GAI (Guardian AI): an advanced AI system that can help protect us from malicious AIs, bad actors, natural disasters, and even our own unintended consequences. GAI could yield a negative P(doom), reducing net existential risk globally below the baseline levels pre-AGI. Our collective goal should be GAI, rather than just AGI. AI alignment should not mean just raw obedience; it must possess deep human understanding and a sense of benevolence. There are many in the AI community trying to create Slave AI, which is fully “aligned” to human values and obeys our every wish exactly. Giving such superpowers to bad actors is clearly not a good idea, but even if we find a way to limit access of such AI to only authorized personnel, it’s pure hubris to believe that any team today has the wisdom to be the final arbiter of universal human value forever. Human values have evolved over time and across borders, and it’s important to preserve that flexibility in AI systems to adapt to a dynamic world and changing value systems.

In fact, I’d much prefer we strive for AI stewardship, versus strict alignment. There are many who argue that less intelligent beings can’t control or influence more intelligent ones. Clearly that’s false, which anyone with a child or pet could attest to. In fact, we all know humans can be highly influenced (some may say “stewarded”) by the very primitive organisms in our body’s microbiome that are significantly less intelligent than us. Even when AGI matures, we should be at least as intelligent to them as bacteria are to us.

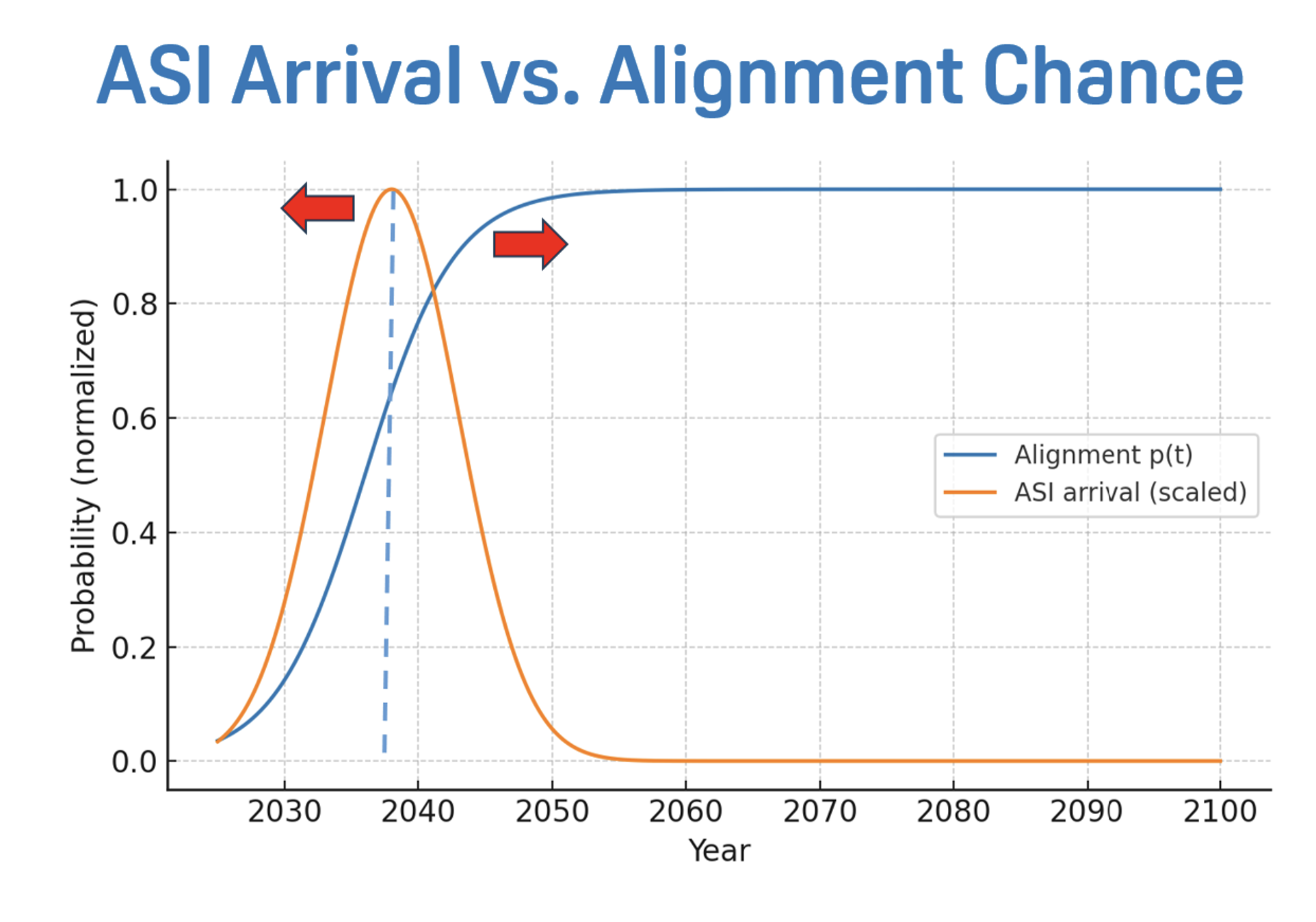

We must remember that P(doom) is not a fixed number; it is a dynamic curve we can affect with our actions. Figure 3 shows AI risk as a function of maturity. Though many may expect it to show a straight line rising toward the top right—risk grows linearly as AI matures—it instead resembles a Kuznets curve:16 While risk increases as AI matures from GOFAI to immature AGI, it should gradually decrease as AI continues to mature to GAI. By recognizing the shared risks all countries will face and supporting cross-border alignment efforts for AGI, we would be delivering an invaluable service to the world.

Figure 3: Kuznets curve of AI risk: a hypothesis.17

V. Cooperation is Enlightened Self-Interest

A pragmatic view—that everyone faces the same AI risks, therefore cooperation is in each party’s self-interest—should motivate immediate trust-building measures, even between strategic rivals. Initial steps might include intelligence-sharing on AI-enabled cyber threats, joint research on AI system auditing, or agreements to ban certain AI applications (akin to chemical/biological weapons treaties). Bifurcating the AI ecosystem into US and Chinese spheres, as current US policies do today, will only create more safe spaces for bad actors to hide and strike, making for a more dangerous world.

“Bifurcating the AI ecosystem into US and Chinese spheres, as current US policies do today, will only create more safe spaces for bad actors to hide and strike, making for a more dangerous world.”

To draw a historical parallel, consider the early nuclear era: Even as the US and USSR were locked in Cold War competition, they shared a mutual interest in preventing nuclear proliferation to third parties and avoiding unauthorized launches. This led to red-phone hotlines, arms control treaties, and, eventually, cooperative threat-reduction programs. In the AI context, preventing AI proliferation to rogue actors could be an arena for US–China collaboration even in the absence of broader political alignment.

It is notable that at the UK’s Bletchley Park AI Safety Summit in November 2023, China formally agreed to work with the US, EU, and others “to collectively manage the risk from artificial intelligence,” signing on to a declaration to “work together and establish a common approach on oversight.”18 Such dialogue must continue and deepen, but sadly, at the 2025 AI Safety Summit, the US and UK were the only countries that didn’t sign the agreement for safer AI.19 If Washington and Beijing can reunite around at least the goal of keeping AI out of terrorists’ hands and preventing catastrophic accidents, it could become a foundation of trust that spills over into more ambitious cooperation.

“If Washington and Beijing can reunite around at least the goal of keeping AI out of terrorists’ hands and preventing catastrophic accidents, it could become a foundation of trust that spills over into more ambitious cooperation.”

How might nations practically collaborate on a technology as sensitive as AGI? Below I offer several possibilities: a multilateral organization that shares research and resources, a game theory approach, a dual-track architecture, and an energy-sharing program.

CERN/ITER for AI

History offers precedents in “big science” projects that transcend borders. The European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), founded in 1954, is a prime example of what’s possible. In the aftermath of World War II, visionary scientists like Niels Bohr pushed for a joint physics laboratory to prevent a brain drain to the US and to rebuild trust among nations. The result—CERN—pooled resources from across dozens of member nations (and over 70 collaborative nations) to pursue fundamental research, from unlocking the secrets of the atom to inventing the World Wide Web. Crucially, CERN’s charter declares that its work is for peaceful purposes and openly shared. As Elliot Jones notes, “CERN represents the post-war ideal of science beyond borders in the service of discovery and peace.”20 Its success in fostering decades of collaboration among countries that had been enemies (France, Germany, the UK, etc.) suggests that common scientific goals can unite even fractious communities.

Today, some policymakers and academics are circulating proposals for a “CERN for AI.” The core idea is an international AI research center where nations contribute talent and funding to jointly develop advanced AI systems in a safe, monitored environment.21 Such a hub could focus on safety research, testing, and compute-heavy projects that no single country might want to or can bear alone. It would embody what one researcher calls “science beyond politics,” providing neutral ground for experts to tackle AI’s challenges without the immediate pressures of commercial or military competition. As with CERN’s particle accelerators, a global AI center might host expensive infrastructure—e.g., massive computing clusters or simulation testbeds—and grant access to all member states’ scientists. This would democratize the “compute power” that is the lifeblood of modern AI, much as CERN democratized access to accelerators. It’s an appealing vision: Instead of an arms race where each player builds its own colossally expensive (and redundant) AI facilities in secret, the world can co-fund a shared platform for controlled AGI development. The EU is already planning such an effort,22 and if the US doesn’t get involved or support it, China would certainly be willing to help. In fact, in late July 2025, just days after the US released its AI Action Plan23 focused on maintaining US dominance over AI, China published its Global AI Governance Action Plan,24 which details its intent to foster global cooperation in a multilateral effort to create and manage a safe, fair, reliable, and controllable advanced AI system that becomes an international public good benefitting humanity.

A similar logic underpins the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) project in nuclear fusion, where the US, China, EU, Russia, and others have coinvested in a giant experimental fusion reactor. Fusion energy, like AGI, was historically seen as a strategic prize, but also a potentially world-changing generator of a public good (limitless clean energy). By working together at ITER, countries share not only costs but know-how, accelerating progress while spreading trust. Yes, these projects are complex and face bureaucratic hurdles, but they demonstrate that even strategic rivals can cooperate in areas of common existential interest. A global AI consortium might involve companies and universities, too—it doesn’t have to consist of governments only—but it should capture the collaborative ethos of CERN or ITER.

Game theory for AI

Importantly, international cooperation need not start at full scale. Game theory teaches us that cooperation can emerge in iterative dynamics. In repeated interactions (like negotiations or joint programs), if each side begins with a small act of trust and reciprocates cooperation, both can steadily build confidence.

In practical terms, an early “trust move” could be the US inviting Chinese AI researchers to observe a safety test, or China sharing medical data to support AI drug discovery research. It is well established that for long-term games like the Prisoner’s Dilemma, the classic tit-for-tat strategy (cooperate on the first move, then mirror your counterpart’s last action) is highly effective in fostering stable cooperation, as it rewards good faith and deters defection.25 Each positive response lays another brick in the foundation. Over time, these small exchanges could lead to more formalized partnerships and increased trust.

“Each positive response lays another brick in the foundation. Over time, these small exchanges could lead to more formalized partnerships and increased trust.”

In game theoretic terms, we want to expand the “shadow of the future”—i.e., make clear that the US, China, and others have a long-term relationship in AI where retaliation to defection is certain and costly, but the rewards of cooperation increase over time, encouraging players to think longer term. Initial tit-for-tat gestures could include reciprocal transparency measures: For instance, both nations could agree to external algorithm audits for bias and safety on a voluntary basis, or to jointly publish research on AI alignment. If one side defects (say, weaponizes a certain AI in a destabilizing way), the other can respond in kind (foreclosing cooperation in that area or imposing sanctions), thus discouraging betrayal. But if both keep cooperating, they reap the benefits of shared progress and avoid reprisals. Unfortunately, today, the US and China operate by the strategy that generates the worst outcomes for both sides: mutual defection.26 The recent Trump-Xi meeting in South Korea gives hope that there’s a softening of tensions and leaves open the door for this type of cooperation, which would not have seemed conceivable in early 2025.

Dual-track engagement

Of course, there are legitimate concerns about sharing certain AI research (e.g., research related to military uses or cybersecurity). The key is to compartmentalize and focus cooperation on the civilian and safety side of AGI. There can be two parallel tracks: Track one is competitive, where each nation will understandably keep some secrets (e.g., security applications of AI, military or defense AI); track two is cooperative, focusing on alignment, safety, health care, and standards that benefit everyone by reducing existential and misuse risks. The US can continue to out-innovate in the competitive track (where democratic institutions and private sector dynamism give it an edge), while also championing cooperation in the safety and public good track. This is not naive idealism but strategic dual-track engagement—fierce competition in some realms, tightly bounded collaboration in others.

Energy as a shared resource

“Under a cooperative AI framework, China could provide sustainable power generation capabilities or equipment to the US for joint AI research, reducing our pressure to build increasingly large power plants, which has been quite challenging given our nearly flat energy production over the last two decades.”

Another opportunity for cooperation is an often-overlooked factor in AGI competition: raw energy capacity. Nations with greater energy generation might support more intensive AI operations. China, for instance, now produces triple the electricity of the United States (3.9 TW vs. 1.34 TW in 2025),27 and the gap is growing quickly. In 2024 alone, China added almost 10 times more new energy generation capacity than the US (~430 GW vs. ~45 GW).28 This energy-generation advantage and rapidly advancing local GPU production could tempt China with a mentality of “we can out-compute you” in an arms race scenario. In a recent speech, Marc Andreessen stated that the future of AI is “physical AI,” where AI and robots are integrated.29 With China’s manufacturing dominance and vast AI talent pool, its longer-term prospects in such a race look bright. China also produces as much top AI researcher talent as the rest of the world combined.30 It’s not inconceivable that China could achieve AGI before the US. Thus, it’s prudent to avoid a direct adversarial relationship on AI with China, given the significant possibility of such a scenario playing out. Under a cooperative AI framework, China could provide sustainable power generation capabilities or equipment to the US for joint AI research, reducing our pressure to build increasingly large power plants, which has been quite challenging given our nearly flat energy production over the last two decades. Moreover, sharing AI insights can prevent redundant efforts in solving the same problems multiple times. China currently leads in all areas of clean energy production technologies31; it is in the US’s interest to have China on our side if the long-term goal is to move our world safely and smoothly into a post-scarcity age. Working with China on joint energy generation and infrastructure projects globally would enable much more rapid and cost-effective deployment, not to mention the environmental benefits.

To summarize, international civilian cooperation on AGI is both feasible and in every major nation’s enlightened self-interest. By learning from models like CERN and ITER, using a tit-for-tat strategy, taking a dual-track approach, and sharing energy resources, we can construct an environment where the focus shifts from racing to the bottom to rising together.

VI. Open-Source AI as a Public Good

One of the strongest arguments for a collaborative rather than adversarial approach to AGI is the notion of open-source and open science. If AGI’s core technologies are developed openly (or at least shared widely among responsible stakeholders), this working model can reduce suspicion, democratize access, and enable more eyes to spot problems. Yann LeCun, the chief AI scientist at Meta and a Turing Award laureate, has been a vocal proponent of open-source AI. He and others point out that if only a few corporations or countries control the most powerful AI models, it would concentrate power dangerously and breed mistrust. Instead, LeCun envisions a world where “we’ll train our open-source platforms in a distributed fashion with data centers spread across the world. Each will have access to its own data sources…but they will contribute to a common model that will essentially constitute a repository of all human knowledge.”32 In LeCun’s view, such a shared global AI model—to which, say, India contributes its diverse languages, the EU contributes its scientific databases, etc.—would far exceed what any one company or nation could build alone, and importantly, everyone would have a stake in it.

LeCun argues that open-source AI should be treated as an international resource, much like the Linux operating system or the World Wide Web, which benefited from global contributions. “Countries have to be really careful with regulations and legislation,” he says, cautioning that governments should “ensure they are not impeding open-source platforms,” but in fact favor and foster them.33 The rationale is that open platforms enable faster innovation (because hundreds of thousands34 of AI developers worldwide can help improve them) and greater security (because transparency allows vulnerabilities to be spotted earlier). This sentiment echoes Yoshua Bengio’s longtime advocacy for “open science.” Bengio noted in a 2021 UNESCO keynote that “we need to have the right agreements…to entice countries to act for the greater good…AI could be really transformative, but it’s not going to happen just based on the forces of markets,” calling for open research frameworks and shared progress rather than siloed efforts.35

“Open-source and multistakeholder development can ensure that an AGI trained on “the repository of all human knowledge” truly incorporates all of humanity, not just a narrow slice.”

Critically, openness also ties into the theme of cultural and global representation. A closed AI system developed by one country might work brilliantly for that country’s language and values but falter elsewhere. The project lead of the “sovereign AI” project for a mid-sized country I recently interviewed expressly complained that the available closed- and open-source AI models just didn’t work well for tasks related to his home language or culture. In other words, if AI is overly controlled by a specific subgroup, it will reflect the biases and blind spots of its creators (i.e., Silicon Valley AI researchers). Current training datasets for LLMs are based on ~90% English content.36 Open-source and multistakeholder development can ensure that an AGI trained on “the repository of all human knowledge” truly incorporates all of humanity, not just a narrow slice. This would help ensure less cultural bias for generative AI outputs in the near term and more holistic thinking when we achieve advanced AGI solutions. Even limited bias or misunderstandings in the models could be accentuated, resulting in dangerous side effects if it devalues certain cultures or peoples while wielding the powers of artificial superintelligence. As the Center for AI Safety report showed, smarter models trained on more complete datasets will automatically find and optimize global utility across the system,37 whereas restricting the scope of training data, as with current bifurcated or sovereign AI methodology, optimizes for local optimums and could in turn create adversarial relationships between nations where none need exist.

Just as we treat roads, power grids, and the internet backbone as critical infrastructure ideally accessible to all, advanced AI might need to be treated as a public good. Open-source projects from the likes of Meta, Mistral, DeepSeek, MiniMax, Moonshot, and Alibaba have already shown the upsides of openness: Global teams can contribute improvements (e.g., making models support more languages or be less biased), and the reduced costs means the technology diffuses more evenly rather than creating extreme winners and losers. Providing the code and weights also means small labs and academics can play a bigger role in contributing advances to the field, and corporations can deploy these models on premise without fear of their proprietary data leaking.

Of course, openness must be balanced with safeguards—one wouldn’t open-source how to build a bioweapon, for example, and similarly dangerous capabilities might need controlled access. But the default orientation should be toward inclusion and transparency, not hoarding. This also builds international trust: If China knows the US is pursuing AI in the open, it will fear surprise leaps less (and vice versa).

“This also builds international trust: If China knows the US is pursuing AI in the open, it will fear surprise leaps less (and vice versa).”

In prior years, open-source models were significantly weaker than closed-source models, but over the last year the gap has narrowed, and if the trends continue, it’s quite possible that open-source models could overtake closed-source models in performance longer-term. When that happens, it’s critical that the US be involved in these open-source efforts. The pressure from the open-source labs has even forced OpenAI to respond with the release of its own less performant open-source model, gpt-oss, in August 2025.38

Just as I’m finalizing this paper in November 2025, the Moonshot Kimi K2 Thinking model39 released, and it’s on par or better than even the leading Western lab frontier models while being capable of running on just two Mac Minis. There is now no more gap, which means the trillions of dollars of the GPU “moat” all those closed labs were building or planning to build over the next few years will need to be completely reevaluated. This could lead to a major stock market adjustment as investors try to figure out where future profits for AI firms (and GPU vendors) will come from when comparable services can be gotten from near zero-margin open-source solutions.

Concrete policy could support open-source AI efforts in several ways. The US government could increase funding for open-source AI research initiatives that involve international collaboration (much as it funds open scientific research), as well as ensure export control regimes don’t inadvertently choke off open academic exchanges (noncommercial research). Nations can even contribute data to a shared pool; one might imagine a “Global AI Data Cloud” where different countries host mirrored nodes of a global pooled training dataset or open model, under agreed governance. Authenticity and accuracy of the data can also be verified upon submission to lessen the chance of misinformation or data poisoning attacks. The EU has already proposed some quite reasonable models for joint data sharing and model co-development.40 While ambitious, this isn’t technically far-fetched—it’s a matter of political will. The upside is a world where startups and students, not just powerful tech giants, can access state-of-the-art AGI models (with appropriate safety guardrails). This would maximize the positive impact of AI (think cures for diseases or climate solutions) by tapping all of humanity’s creativity, not just a privileged few.

In summary, open-source and open-access AI systems act as force multipliers of global benefit and trust. They mitigate the concentration of power, reduce international suspicion by making development more transparent, and incorporate diverse values and ethics systems into AI, which in turn improves alignment with human norms more broadly The US should embrace this by supporting open-source AI platforms and resisting pressures to over-classify or over-restrict AI basic research. The US’s recent AI Action Plan does include clauses that appear to encourage open-source AI, but the wording seems to suggest it purely as a countermeasure to deter diffusion of Chinese open-source models, rather than as a push for true open collaboration on AI globally.

VII. Domestic Readiness

“For the US to lead by example in the AGI era, it must demonstrate a model of inclusive adaptation at home, ensuring its population is equipped to thrive alongside intelligent machines and that the benefits of AI don’t just accrue to a narrow elite.”

Global cooperation is vital, but it cannot succeed without domestic preparedness. In the United States, the advent of AGI will exacerbate existing societal challenges (job displacement, inequality, regional economic divides) unless proactive measures are in place. For the US to lead by example in the AGI era, it must demonstrate a model of inclusive adaptation at home, ensuring its population is equipped to thrive alongside intelligent machines and that the benefits of AI don’t just accrue to a narrow elite. This is where forward-looking policies like Universal Basic Infrastructure and Income (UBII), massive reskilling initiatives, and open access to AI tools come in. In “America is Running the Wrong AI Race,”41 I critique the White House’s AI Action Plan by explaining why the US can’t focus all its energy chasing raw innovation speed alone. Without putting in place a proper social safety net, updating needed infrastructure, and ensuring AI safety to enable a smooth transition to mass AGI deployment, “the faster we achieve AGI, the faster we create chaos within the nation.”42 In fact, other nations that make the appropriate preparation in time could leapfrog the US (and China) by avoiding the ensuing societal chaos we will create for ourselves.

Universal Basic Infrastructure and Income

UBII extends the concept of Universal Basic Income (UBI) by also guaranteeing every citizen access to essential services and infrastructure needed in a high-tech economy. This means not only a baseline monetary income to buffer against job displacement, but also things like universal high-speed internet, affordable health care, quality education, and even access to AI computing resources—the basic underpinnings of modern economic participation. As AI potentially increases productivity exponentially, we can afford to provide a safety net and a springboard. Think of UBII as ensuring no American is left behind in the AGI transition. This is not just a social policy but a strategic investment. UBII directly addresses the looming financial and social deficiencies facing AI-displaced families by giving people the freedom to pursue their passions while disincentivizing antisocial behavior. Notably, UBII is about empowerment, not idleness. Another way to think about this is, “UBII isn’t being paid to do nothing…it’s being paid to do what you love.”43

In practical terms, a US government embracing UBII might, for example, provide a monthly stipend to every adult (ensuring basic consumption needs are met as traditional jobs evolve or disappear). Simultaneously, it would fund major upgrades in public infrastructure: nationwide high-speed connectivity, AI-equipped public libraries and community colleges, and perhaps even public AI supercomputing centers where anyone can leverage powerful compute for projects (just as how public libraries have given people access to information they can’t afford individually).44 Some of this is already hinted at in legislation; the recently launched National AI Research Resource (NAIRR) pilot is a step toward democratizing AI R&D, providing researchers with access to advanced computing, datasets, and tools as a “shared research infrastructure.” As the National Science Foundation’s director Sethuraman Panchanathan said, “to continue leading in AI R&D, we must create opportunities across the country to advance AI innovation…empowering the nation to shape international standards.”45

“The US needs to launch something akin to a “GI Bill for the AI Age”—large-scale programs to retrain all affected workers for the new kinds of jobs needed post-AGI, ensuring that the ones who don’t find new jobs are taken care of and everyone is provided a roof over their heads.”

Social safety nets and reskilling for the AI age

We’re not new to ensuring a smooth transition with a social safety net. In 1944, in anticipation of over ten million military personnel reintegrating into society after WWII, the US legislature passed the landmark Servicemen’s Readjustment Act (known as the GI Bill), which covered college tuition, books, a monthly stipend, home and business loans, and extended unemployment compensation to a full year. The number of college graduates doubled from 1940 to 1950 as a direct result of the bill. The US needs to launch something akin to a “GI Bill for the AI Age”—large-scale programs to retrain all affected workers for the new kinds of jobs needed post-AGI, ensuring that the ones who don’t find new jobs are taken care of and everyone is provided a roof over their heads. For this coming disruption, the impacted number won’t just be ten million but maybe an order of magnitude bigger.46 To avoid widespread social unrest, every worker whose job is threatened by automation (ranging from truck drivers with autonomous vehicles to accountants with AI bookkeeping, and more) should have access to free training in growing fields, whether technically oriented or entirely new creative and service roles that emerge. The private sector can be incentivized via tax credits to retain, hire, or retrain existing workers rather than opt for rapid staff reduction. Even new graduates are not safe from displacement. In fact, it’s likely that the younger, less experienced workers will be the first major group AI will replace. Current AI systems may not be able to do the work of skilled mid-career workers, but when used properly, they are already able to do much of the work of junior white-collar staff at little more than the cost of electricity, and those capabilities are growing daily. Some recent data already show the divergence of new graduate unemployment from historical trends. For the first time in decades, new graduate unemployment is surpassing national averages.47 The plight of Gen Z and Gen Alpha workers will become even more visible within one to two years.48 Brynjolfsson et al.’s recent paper “Canaries in the Coal Mine” had similar findings, showing strong correlation of reduced hiring in areas exposed to AI automation, especially for junior positions.49 There’s already early signs that this trend has started to affect mid-career workers and continue to move up the ladder as the systems improve.

“If AGI handles more cognitive heavy lifting, human jobs will shift toward what we uniquely bring—context, ethics, empathy, compassion, and leadership.”

We should also revamp K–12 and higher education to emphasize skills that complement AI, such as creativity, critical thinking, emotional intelligence, and interdisciplinary literacy. If AGI handles more cognitive heavy lifting, human jobs will shift toward what we uniquely bring—context, ethics, empathy, compassion, and leadership. As our economy becomes increasingly automated, we need to teach our population to reclaim their humanity. Investing in human capital is also a security imperative: It will maintain public support for an AI-driven economy (preventing social backlash from job displacement and purposelessness) and ensure social stability throughout the country. Many will ask: How can we afford such programs? The real question should be, “Can we afford not to provide these needed programs?” Our leaders in the 1940s understood why we needed them, and the reasons are even truer now.

Redirecting part of our trillion-dollar defense budget (about $2.7 trillion globally in 202450 and rising quickly) could help. Only $300 billion a year could eliminate extreme poverty on the planet. New AI and robotics productivity taxes will likely be needed to make rapid mass layoffs less palatable. Universal Basic Capital (UBC) programs like the ones in Norway or Alaska could be added to the mix, where dividends from natural resources (or AI productivity gains) can be reinvested and distributed to the population of the region to help fund such support programs. Collaboration with other nations could add to the solution—e.g., exchanging best practices on apprenticeship and reskilling programs, creating joint programs on driving down health care costs, or encouraging foreign direct investment and tech transfer into the country. Education and health care are two of the biggest and most quickly increasing parts of US household spending, which could be reduced significantly if we can streamline operations, as already exists in other nations. The EU and China are also grappling with reskilling and social stability issues, thus sharing solutions for a common enemy could help rebuild lines of cooperation. The world united against the common threat of ozone depletion in the 1980s and 1990s with the successful joint execution of the Montreal Protocol, but the shared threat of societal breakdown from AI may actually be a more salient danger. Additionally, as AI and robotics drive down marginal costs for core goods and services, there will be deflationary forces at play, reducing the funding burden over time for most of life’s necessities.

“The world united against the common threat of ozone depletion in the 1980s and 1990s with the successful joint execution of the Montreal Protocol, but the shared threat of societal breakdown from AI may actually be a more salient danger.”

From a global perspective, as most emerging markets are less exposed to AI displacement near term and are starting from a lower cost basis, finding and building workable funding solutions for those populations over time may be less challenging than in the developed world. Integrating Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) into the deployment process could also help provide a low-overhead mechanism for mass distribution to the broad population, and using its programmability capabilities could minimize fraud and abuse. Early pilots in China have shown this could be viable.

America as a leader in international governance

Lastly, trust-building with China and the EU at a governmental level need parallel trajectories. With Europe, the US should deepen partnerships around AI ethics and regulation—for instance, aligning on standards for transparency and privacy (Europe’s GDPR and AI Act are influential). With China, a more delicate but crucial engagement is needed. This could involve reestablishing formal science and technology dialogues that have waned in recent years, even forming a US–China Joint Commission on AI Safety. Confidence-building measures might include reciprocal lab visits by scientists, a direct hotline between national AI research centers to quickly clarify any incidents (analogous to the Cold War hotlines to avoid accidental escalation), and pre-agreed “rules of the road” for military AI (such as not integrating AGI into nuclear command and control). The Bletchley Park summit mentioned earlier was an encouraging sign—a Chinese vice minister stood alongside US and EU leaders in affirming the need for a common AI governance approach.51 China’s Global AI Governance Action Plan proposes working with the UN to actively safeguard personal privacy and data security; enhance the diversity of AI data corpora; eliminate discrimination and bias; and promote, protect, and preserve the diversity of the AI ecosystem and human civilization.52 Building on these, the US could invite China into a permanent working group on frontier AI safety, perhaps under the auspices of the UN or G20, to institutionalize cooperation. Meanwhile, working with allies like Japan, South Korea, India, and others to create a united front on responsible AI use will set healthy expectations globally. Expecting the world to cooperate on making AI smarter is likely too much to ask right now, but working together to make AI safer should be a more achievable starting point.

Domestic social stability is a prerequisite for credible global leadership; without it, the US will export volatility. This internal strength and integrity, in turn, give it the moral authority needed to coax other nations toward a long-term collaborative framework.

VIII. Global AI Alignment Requires Global Input

Aligning AGI with human values is often cited as the foremost technical challenge: How do we ensure a machine intellect respects ethical principles and the richness of human morals? A key insight is that “human values” are not monolithic—they are pluralistic and culturally diverse. An AGI trained only on Western data, for instance, might unconsciously imbibe Western biases and blind spots, potentially leading to misunderstandings or offenses when deployed in non-Western contexts. Thus, as discussed earlier in this paper, achieving true global alignment demands culturally representative datasets and international input in AGI training and governance.

“No single nation can adequately foresee all the contexts in which AGI will operate; international collaboration isn’t just a nice-to-have but is functionally necessary to cover the full range of human conditions an AGI may encounter.”

Consider language as an analogy: If you train an AI only on English sources, it will perform poorly in understanding, say, Mandarin Chinese queries or idioms—not just linguistically, but contextually. The same is true for ethics and norms. There are deeply ingrained differences, for example, in Eastern versus Western philosophy on issues like individualism versus collectivism, or the boundary between privacy and community safety. If AGI is to navigate the complexities of the world’s concerns, it must be educated by the world’s societies. Demis Hassabis of Google DeepMind emphasized that AGI, by its nature, “is across all borders. It’s going to get applied to all countries”; hence, “the most important thing is it’s got to be some form of international cooperation” shaping its development.53 In other words, no single nation can adequately foresee all the contexts in which AGI will operate; international collaboration isn’t just a nice-to-have but is functionally necessary to cover the full range of human conditions an AGI may encounter.

European leaders have already raised concerns that major AI models reflect predominantly American norms (for instance, about free speech limits or fairness criteria). Likewise, experts from the Global Majority nations often point out that AI systems often perform poorly for their communities—e.g., facial recognition misidentifies darker skin, or medical AI lacks data on diseases prevalent outside rich countries. To fix this, AGI training data must be as globally sourced as possible—including texts, art, histories, and dialogues from all cultures—and the teams building and tuning AGI should themselves be diverse and international.

Global input also matters for legitimacy. Imagine an AGI governance regime created only by the US and Europe—other nations would understandably be wary or feel dictated to. In contrast, if the alignment protocols or safety guidelines for AGI come from a multilateral process (say, UNESCO or a new global body), they’re more likely to be adopted everywhere. There is precedent here: The human genome project involved contributions from many countries, ensuring shared ownership of the breakthroughs. For AGI, we might convene an International AGI Ethics Council with representatives from different philosophical and religious traditions to hash out common ground principles (e.g., respect for life, fairness, do no harm) that an AGI should uphold. This is akin to creating a “constitution” for AGI with worldwide buy-in, rather than having one superpower unilaterally program the AI that everyone else must then live with.

“If AGI can enable any person or country to communicate with any other in real time with full native context, it could reduce the misperceptions that fuel conflict.”

It’s worth noting that China and other nations are not inherently opposed to this idea. In AI ethics forums, Chinese scholars often emphasize harmony and societal responsibility—values that align well with global benefit. In fact, Chinese officials spoke of helping to build an international “governance framework” for AI.54 If the US extends an open hand for genuine collaboration on alignment, it’s likely to find many takers. After all, every country has a lot to lose if AGI goes wrong (be it via runaway AI or its destabilizing impact) and a lot to gain if AGI can be directed to solve global problems like climate change, hunger, disease, or poverty.

Another intriguing notion is using AGI itself to foster global understanding—for example, deploying advanced AI as a cultural bridge for conflict resolution. If AGI can enable any person or country to communicate with any other in real time with full native context, it could reduce the misperceptions that fuel conflict. This could be a major aid to diplomatic issues around the world or even in bridging political divides domestically. But reaching that point safely requires that the AGI is not overly skewed to one worldview. Albania’s recent push to install a digital AI minister in its government and mandatory use of an AI advisor for each human member of its parliament could be a great example of how AI could be applied to improve national and international governance.55

In summary, global alignment means global involvement. By ensuring a rich tapestry of human input into AGI’s formation, we can increase the odds it will respect the cultural nuances when making decisions, and can avoid misuse by bad actors seeking to divide or harm various groups or individuals. If we train AGI with only one nation or culture’s narrative (as is proposed in the US’s AI Action Plan), it will see all other groups as enemies and act accordingly. Figure 4 visually depicts the predicament we are exacerbating with our race mentality. We should seek as much overlap between the two curves in the figure as possible to allow for a safer outcome if/when we achieve AGI/ASI. Our current policies, though, are forcing the curves even further apart: They hasten ASI arrival and deemphasize AI safety by deregulating the sector, forcing a race condition that can only lead to a more dangerous world.

Figure 4: ASI arrival time vs. alignment probability (arrows represent the effect of current policies).

IX. Architecting a Post-AGI Framework

At pivotal moments in history, the United States has stepped up to build systems of cooperation that transcend rivalry. After World War II, rather than punishing its adversaries or retreating to isolation, America invested in rebuilding Europe and Japan through the Marshall Plan and related programs. This not only averted economic collapse and Communist revolution in those regions, but also cemented alliances and created a foundation for decades of peace and prosperity (and markets for US goods, incidentally). It was a triumph of enlightened self-interest. Similarly, during the Cold War, even as the US and USSR stockpiled arms, they also forged unprecedented agreements—from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) to Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) and the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START)—that put guardrails on the arms race and involved nearly every nation in preventing nuclear war. American diplomats and visionaries like Vannevar Bush, J. Robert Oppenheimer, George Marshall, and, later, Henry Kissinger recognized that certain dangers (like nuclear holocaust) and certain opportunities (like global economic development) could only be addressed by cooperative architectures rather than unilateral action. The lessons of SALT and START are relevant now more than ever: Restraint is not a sign of weakness; it is the most rational strategy for survival in a world full of existential risks.

“The lessons of SALT and START are relevant now more than ever: Restraint is not a sign of weakness; it is the most rational strategy for survival in a world full of existential risks.”

Today, we stand at a similar crossroads with AGI. This technology could be as disruptive as the atomic bomb in its strategic implications, and as transformative as electricity or the internet in its societal impact. If we treat it purely as a domain of competition—a new space race or arms race—we risk repeating the darkest aspects of the 20th century’s struggles, possibly with worse consequences given AI’s potential ubiquity.

What might a Marshall Plan for the AI era look like? It would entail the US spearheading a massive international investment not only in rebuilding physical infrastructure, but in building digital and human infrastructure worldwide. For instance, the US could lead a consortium to fund AI-driven education and health care solutions in emerging markets, effectively exporting the benefits of AGI to every corner of the globe. This would win hearts and minds much more effectively than any propaganda. If a farmer in Africa or a teacher in South Asia sees their livelihood improved by an American-led AGI initiative (co-created with local input), they become a stakeholder in the success of a cooperative international system. This AI Marshall Plan could also include debt forgiveness or grants tied to technological leapfrogging, helping countries install smart power grids, climate resilience systems, or precision agriculture, all powered by AI. Such generosity is not purely altruistic: It would diminish the breeding grounds for conflict (poverty, despair) and create partners in maintaining a stable world. The US can learn from this part of China’s soft power strategy, akin to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). If we’re concerned about the high costs of such a program, it’s likely China and even the EU could be convinced to jointly finance it.

On the governance side, the US should use its still-considerable diplomatic clout to shape global treaties or agreements on AI before mistrust curdles into an AI Cold War. One model could be a Global AGI Charter, where nations pledge to use AGI for peaceful purposes only and to cooperate on safety. Verification mechanisms (analogous to nuclear inspections) could be devised for certain high-risk AI activities; for example, international observers could be invited to major AGI training facilities to certify they are complying with agreed-upon safety protocols. It sounds far-fetched, but recall that at one time letting foreigners inspect a nation’s missile silos also sounded impossible, yet it became routine under arms control treaties. The US could also advocate for an expansion of the UN’s mandate to include an “International AI Agency”, something like an International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) but for AI, which could monitor and advise on AI developments worldwide and help coordinate response to any AI crises. One researcher recently argued that establishing an international AI authority, akin to IAEA/CERN/ITER, will require blending diverse skill sets and securing buy-in, as those earlier institutions did.56 The US is well positioned to drive this conversation, given its experience in setting up post-war institutions (e.g., the UN, IMF, World Bank, etc.).

“The traditional American ideals of freedom, openness, and innovation are better advanced by an open-world system where AGI is abundant and benefit-sharing, rather than a closed-world system of silos and suspicion.”

Crucially, none of this means the US abandons its values or national interests—on the contrary, it means projecting them in a sustainable way. The traditional American ideals of freedom, openness, and innovation are better advanced by an open-world system where AGI is abundant and benefit-sharing, rather than a closed-world system of silos and suspicion. A cooperative stance does not mean being naive about verification or about hedging against defection (trust but verify). But it does mean believing in the possibility of win-win outcomes. One might recall that the United States in 1945 had the sole atomic bomb and could have tried to dictate terms to the world, but instead it helped create rules and organizations that bound even itself, because enlightened leaders knew that rule of law and mutual prosperity were the true sources of security. The US currently still holds a lead in many AI metrics, and should leverage this lead to set norms and institutions that make the whole world safer and better, rather than seek a permanent domination that would be unstable and morally dubious.

X. Conclusion

The geopolitical moment of AGI in 2025 echoes the late 1940s. Then, we had a choice between division and unity, and the US championed unity with remarkable success over the long term. Now, as AGI looms, we must choose again. Will we slide into a wary bipolar or multipolar contest, racing toward an uncertain conclusion with no possible winner? Or will we, guided by foresight, establish a new architecture of alignment and cooperation that channels this technology for universal benefit? The answer lies partly in whether we can imagine a positive-sum future and act to realize it. A more abundance-minded framework57 could help provide some structured guidance on how we can adapt to a post-scarcity age for humanity. But we need to act in the next few years before AGI is fully realized. All this must start with a change in our mindset to one that understands the world is not zero-sum and cooperation is not weakness. Rather than an unfettered race to be first at building a risk-prone sovereign AGI, the world needs to rally around a common goal of building a benevolent Guardian AI that protects us not only from bad actors and natural disasters, but also from the unintended consequences of our own actions. The benefits of AI must be shared with all peoples of the world, rather than be hoarded by a few elites. We must prepare ourselves and the entire world to smoothly transition into a post-labor economy, or we will have chaos in the streets. The US played a critical role in rebuilding and stabilizing the world after WWII. It must rise to the occasion again and be a uniting force for the world at this critical juncture in history.

That is also the spirit behind Stanford’s Digitalist Papers, which aspire to outline a blueprint for global AGI governance, a foundation on which a new global alignment architecture can rise.58 By moving beyond rivalry, the United States with China (and all global stakeholders) together can co-author a future where AGI is remembered not as a battleground but as the cornerstone of a new era of collective human advancement. It will not be easy to put aside our engrained instincts, but it is possible and necessary. History shows security without solidarity is brittle. We must build a common guardian together, or be at the mercy of chance.

“By moving beyond rivalry, the United States with China (and all global stakeholders) together can co-author a future where AGI is remembered not as a battleground but as the cornerstone of a new era of collective human advancement.”

Appendix A

Table 1: Summary of AI Type Definitions and Associated Risks

Appendix B

Figure 5: Net risk by AI taxonomy.

Appendix C

Two directions compete for policymaking today. The dominant policy narrative is focused on national advantage, and some experts advocate focusing on tool AI and sovereign AI to make the world safer. However, when objectively evaluating the risks, safety and prosperity lie in Guardian AI—smarter aligned systems that do not blindly obey us, but instead can preemptively protect us from threats we don’t yet see. To reach GAI, world leaders need to take a longer-term, holistic policy path to bring lasting benefits to their nation, and the world.

Table 2: Comparison of Two Competing Directions for AI Policymaking

1. Artificial general intelligence (AGI) has recently been referred to as “TAI” by some, as it is in other essays in this volume. To avoid confusing the reader, the term AGI will be used in the rest of the paper.

2. The author acknowledges the indispensable feedback in the writing of this paper from Erik Brynjolfsson, Sandy Pentland, Daniel Susskind, Susan Young, Max Baucus, Robert Kapp, Lola Woetzel, Gary Rieschel, Andy Rothman, Josh Lipsky, Michael Gusek, James C. Kralik, and others.

3. The White House, “America’s AI Action Plan” (July 2025), https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Americas-AI-Action-Plan.pdf.

4. Jerome C. Glenn, “Why AGI Should Be the World’s Top Priority,” Horizons: Journal of International Relations and Sustainable Development 30 (Spring 2025), https://www.cirsd.org/en/horizons/horizons-spring-2025--issue-no-30/why-agi-should-be-the-worlds-top-priority.

5. Glenn, “Why AGI Should Be the World’s Top Priority.”

6. Alvin Graylin and Paul Triolo, “There Can Be No Winners in a US-China AI Arms Race,” MIT Technology Review, January 21, 2025, https://www.technologyreview.com/2025/01/21/1110269/there-can-be-no-winners-in-a-us-china-ai-arms-race/.

7. Video Generation Model Arena Leaderboard, Artificial Analysis, accessed October 10, 2025, https://artificialanalysis.ai/text-to-video/arena?tab=leaderboard; LLM Leaderboard, Verified AI Rankings, accessed October 10, 2025, https://llm-stats.com/.

8. Artificial Analysis, AI Model & API Providers Analysis | Artificial Analysis, accessed November 5, 2025, https://artificialanalysis.ai.

9. Matt Crump, “Yoshua Bengio’s Vision for AI: Balancing Innovation with Ethical Responsibility,” 1950.ai, January 31, 2025, https://www.1950.ai/post/yoshua-bengio-s-vision-for-ai-balancing-innovation-with-ethical-responsibility.

10. Alvin Graylin, “The US–China AI Arms Race,” Committee for the Republic Salon, YouTube, May 28, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jg6brPvFJGw.

11. Nick Bostrom, “Ethical Issues in Advanced Artificial Intelligence,” 2003, https://nickbostrom.com/ethics/ai.

12. JoshuaFox et al., “Computronium,” LessWrong, November 18, 2012, https://www.lesswrong.com/w/computronium.

13. Mantas Mazeika et al., “Utility Engineering: Analyzing and Controlling Emergent Value Systems in AIs,” preprint, arXiv, February 19, 2025, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2502.08640.

14. Sara Brown, “Why Neural Net Pioneer Geoffrey Hinton Is Sounding the Alarm on AI,” MIT Sloan, May 23, 2023, https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/why-neural-net-pioneer-geoffrey-hinton-sounding-alarm-ai.

15. International AI Safety Report: The International Safety Report on the Safety of Advanced AI (AI Action Summit, January 2025), https://securesustain.org/report/international-ai-safety-report-2025/.

16. Saddique Ansari, “The Kuznets Curve,” Economics Online, June 19, 2023, https://www.economicsonline.co.uk/definitions/the-kuznets-curve.html/.

17. Alvin Graylin, “Kuznets Curve for AI Risk,” AWE, YouTube, June 20, 2024, https://youtu.be/ZBIxYeu_wqQ?si=MEW2siwrZPM8qoLv.

18. Paul Sandle and Martin Coulter, “AI Safety Summit: China, US, and EU Agree to Work Together,” Reuters, December 1, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/technology/britain-brings-together-political-tech-leaders-talk-ai-2023-11-01/.

19. Zoe Kleinman and Liv McMahon, “UK and US Refuse to Sign International AI Declaration,” BBC, February 11, 2025, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c8edn0n58gwo.

20. Elliot Jones, “A ‘CERN for AI’—What Might an International AI Research Organization Address?,” in Alex Krasodomski, ed., Artificial Intelligence and the Challenge for Global Governance (Chatham House, June 2024), https://www.chathamhouse.org/2024/06/artificial-intelligence-and-challenge-globalgovernance/02-cern-ai-what-might-international.

21. Jones, “A ‘CERN for AI.’”

22. Alex Petropoulos et al., Building CERN for AI: An Institutional Blueprint (Centre for Future Generations, 2025), https://cfg.eu/building-cern-for-ai/.

23. The White House, “America’s AI Action Plan.”

24. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Global AI Governance Action Plan,” People’s Republic of China, July 26, 2025, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/eng/xw/zyxw/202507/t20250729_11679232.html.

25. Eric Estevez, “What Does Tit for Tat Mean, and How Does It Work?,” Investopedia, February 27, 2024, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/t/tit-for-tat.asp.

26. Estevez, “What Does Tit for Tat Mean, and How Does It Work?”

27. Renewables Capacity Doubles in First Half," China Daily, July 31, 2025, https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/statistics/202507/31/content_WS688ae199c6d0868f4e8f490d.html; U.S. Energy Information Administration, "Electric Power Monthly," December 23, 2025, https://www.eia.gov/electricity/monthly/epm_table_grapher.php?t=table_6_01.

28. US Energy Information Administration, “Today in Energy,” accessed February 13, 2025, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=64705; Carolyn Wang, “Monthly China Energy Update,” Climate Energy Finance, February 2025, https://climateenergyfinance.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/MONTHLY-CHINA-ENERGY-UPDATE-Feb-2025.pdf.

29. Marc Andreesen, “From ChatGPT to Billions of Robots,” interview with Joe Lonsdale at the 2025 Reagan National Economic Forum, Joe Lonsdale: American Optimist, YouTube, May 30, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pRoKi4VL_5s.

30. “The Global AI Talent Tracker 2.0,” Macro Polo, accessed October 10, 2025, https://archivemacropolo.org/interactive/digital-projects/the-global-ai-talent-tracker/.

31. Statista, “Leading Countries in Installed Renewable Energy Capacity Worldwide in 2024,” July 2025, https://www.statista.com/statistics/267233/renewable-energy-capacity-worldwide-by-country/.

32. Lakshmi Varanasi, “Meta’s Chief AI Scientist Says All Countries Should Contribute Data to Shared Open-Source AI Model,” Business Insider, May 31, 2025, https://www.businessinsider.com/meta-yann-lecun-shared-open-source-aimodel-2025-5.

33. Varanasi, “Meta’s Chief AI Scientist Says All Countries Should Contribute Data to Shared Open-Source AI Model.”

34. Xinhua, “Report Shows US, China Make Up 60pct of Global AI Researchers,” XinhuaNet, July 4, 2025, https://english.news.cn/20250704/b426995bb64e4bf3ba3df1068fa113f9/c.html.

35. Ciarán Daly, “Bengio: Open Science and International Cooperation Key to AI for Good,” AI Business, February 18, 2021, https://aibusiness.com/responsible-ai/bengio-open-science-and-international-cooperation-key-to-ai-for-good.

36. Toms Bergmanis, “The LLM Data Dilemma: Ocean of Dirt or Drop of Gold?,” Tilde, January 22, 2025, https://tilde.ai/the-llm-data-dilemma/.

37. Mazeika et al., “Utility Engineering: Analyzing and Controlling Emergent Value Systems in AIs.”

38. OpenAI, “Introducing gpt-oss,” August 5, 2025, https://openai.com/index/introducing-gpt-oss/.

39. Julian Horsey, “Kimi K2 Thinking Leaps Ahead: Open Model Beats OpenAI & Google in Tests,” Geeky Gadgets, November 7, 2025, https://www.geeky-gadgets.com/kimi-k2-thinking-open-source-llm/.

40. Petropoulos et al., Building CERN for AI: An Institutional Blueprint.

41. Alvin Graylin, “America Is Running the Wrong AI Race,” Abundanist: A Post-Scarcity Community, Substack, July 2025, https://abundanist.substack.com/p/america-is-running-the-wrong-ai-race.

42. Graylin, “America Is Running the Wrong AI Race.”

43. Alvin Graylin, “Abundanism: A New Philosophy for a Post-Scarcity World,” Abundanist: A Post-Scarcity Community, Substack, May 13, 2025, https://abundanist.substack.com/p/abundanism.

44. Alvin Graylin, “A ‘Bill of Rights’ for the Age of AI,” Abundanist: A Post-Scarcity Community, Substack, July 2025, https://abundanist.substack.com/p/a-bill-of-rights-for-the-age-of-ai.

45. US National Science Foundation, “Democratizing the Future of AI R&D: NSF to Launch National AI Research Resource Pilot, January 24, 2024, https://www.nsf.gov/news/democratizing-future-ai-rd-nsf-launch-national-ai.

46. Statista, “Monthly Civilian Labor Force in the United States from August 2023 to August 2025,” accessed November 7, 2025, https://www.statista.com/statistics/193953/seasonally-adjusted-monthly-civilian-labor-force-in-the-us/#statisticContainer.

47. Christopher Rugaber, “Unemployment Among Young College Graduates Outpaces Overall US Joblessness Rate,” AP News, June 26, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/college-graduates-job-market-unemploymentc5e881d0a5c069de08085a47fa58f90f.

48. Erik Brynjolfsson, Bharat Chandar, and Ruyu Chen, “Canaries in the Coal Mine? Six Facts About the Recent Employment Effects of AI,” Stanford Digital Economy Lab, August 26, 2025, https://digitaleconomy.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Canaries_BrynjolfssonChandarChen.pdf.

49. Ileana Exaras, “Military Spending Worldwide Hits Record $2.7 Trillion,” United Nations News, September 9, 2025, https://news.un.org/en/story/2025/09/1165809.

50. Rugaber and AP, “Unemployment Among Young College Graduates Outpaces Overall US Joblessness Rate”; data from New York Federal Reserve, June 2025.

51. Sandle and Coulter, “AI Safety Summit: China, US, and EU Agree to Work Together.”

52. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC, “Global AI Governance Action Plan.”

53. “Google Deepmind CEO Says Global AI Cooperation ‘Difficult,’” Economic Times CIO, June 3, 2025, https://cio.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/artificial-intelligence/google-deepmind-ceo-says-global-ai-cooperationdifficult/121586072.

54. Sandle and Coulter, “AI Safety Summit: China, US, and EU Agree to Work Together.”

55. “Albania’s AI Minister is ‘Pregnant’ with 83 Digital Assistants, Prime Minister Says,”EuroNews, October 30, 2025, https://www.euronews.com/next/2025/10/30/albanias-ai-minister-is-pregnant-with-83-digital-assistants-prime-minister-says.

56. Mark Robinson, “The Establishment of an International AI Agency: An Applied Solution to Global AI Governance,” International Affairs 101, no. 4 (July 2025): 1483–1497, https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiaf105.

57. Graylin, “Abundanism: A New Philosophy for a Post-Scarcity World.”

58. Erik Brynjolfsson, Alex Pentland, Nathaniel Persily, Condoleezza Rice, and Angela Aristidou, eds., The Digitalist Papers (Stanford Digital Economy Lab, 2024).