Resilient by Design: Dual Safety Nets for Workers in the AI Economy

How can we respond to the impact of transformative AI on the labor market? In this essay, Ioana Marinescu sets out a two-tiered response, recognizing the immense uncertainty about what lies ahead: “adjustment insurance” to help workers who suffer transitory job losses, and a “digital dividend” to support those who might find themselves more permanently without work. Importantly, the latter can be scaled up and down, as we learn more about the challenge we face.

I. Introduction

Artificial intelligence could automate whole classes of tasks, displacing many workers even as new jobs are created, and thus could transform the structure of employment. In the literature, the term “transformative AI” (TAI) refers to the possibility that AI could reshape the economy and society on a scale comparable to the Industrial Revolution. Even if AI falls short of this scale, its widespread adoption as a general-purpose technology will significantly change the kinds of jobs we do and necessarily lead to some job losses as workers are reallocated across sectors.

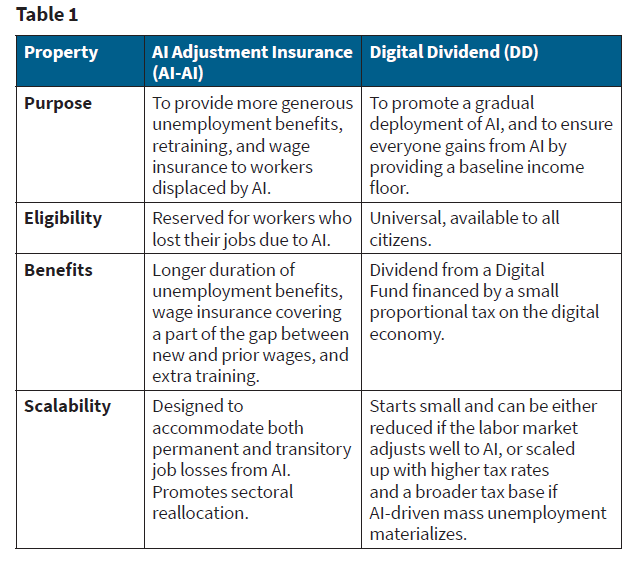

History shows that those who lose their jobs seldom glide into new positions; persistent earnings losses are the norm. What policies should we consider to help workers affected by AI and make sure the benefits of AI are broadly shared? Policymakers often worry that generous support could discourage work. Yet research suggests such effects are generally limited, and the concern becomes less relevant if AI leads to durable, economy-wide job scarcity. Given the uncertainty about AI’s labor market effects, it is important to consider flexible approaches to worker support. In a scenario where AI only causes short-lived increases in unemployment, the focus is on insuring workers against income loss while promoting employment and worker reallocation across sectors. At the other extreme, in a scenario where AI causes large-scale and persistent joblessness, the focus of worker support is on an income guarantee rather than insurance, with less emphasis on employment promotion. To accommodate different scenarios, I outline a two-tier architecture. The AI Adjustment Insurance (AI-AI) extends unemployment benefits and provides retraining and wage insurance to workers displaced by AI. The Digital Dividend (DD) is a small universal cash benefit financed by a tax on the digital sector, and serves as a scalable pathway toward higher unconditional income support, should economy-wide job scarcity materialize. The combination of a conditional and time-limited program (AI-AI) and a scalable unconditional program (DD) could build worker resilience in the face of AI, no matter the ultimate employment effects. These policy blueprints are designed to provide flexible solutions to address the job losses and the broader transformation of employment that AI may bring.

II. Policy Blueprints: AI Adjustment Insurance and the Digital Dividend

Insuring workers during the transition: AI Adjustment Insurance

Imagine losing your job to a chatbot; AI Adjustment Insurance (AI-AI) would step in here, offering support as you look for what’s next. AI-AI would be reserved for workers who are determined to have lost their jobs due to AI. An AI Adjustment Insurance system would provide more generous unemployment insurance, while facilitating the reallocation of workers to new jobs. First, it would offer these workers a longer duration of unemployment benefits: This part of AI-AI would protect them and their families against the adverse effects of income loss. Second, to encourage workers to take new jobs faster, even if these jobs pay less than their prior jobs, AI-AI would offer wage insurance, a kind of employment subsidy for workers. Specifically, when there is a gap between their new wage and their prior wage, wage insurance would cover a significant part of this gap for a certain period of time, e.g., 70% of the gap for two years. Think of it as a temporary raise that softens the blow if your new job pays less, covering most of the pay cut for up to two years. Finally, AI-AI would offer extra training, which helps better prepare workers for new jobs and decreases the likelihood that they will have to take a job with pay significantly below what they used to get.

“An AI Adjustment Insurance system would provide more generous unemployment insurance, while facilitating the reallocation of workers to new jobs.”

To sum up, AI-AI provides:

1. More generous unemployment benefits: longer duration of benefits.

2. Wage insurance: covers a percent of the gap between the new wage and the prior wage for a limited period.

3. Extra training.

Policies with similar features to AI-AI have shown promising results. Longer unemployment benefits will not significantly increase unemployment (for more on this, see Section III) if the overall unemployment rate is already high,1 and job training is a well-established policy to boost the earnings and employment prospects of the unemployed.2 The Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) is a cost-effective policy with the same three features as the proposed AI-AI, but applied to workers who lost their jobs due to trade. The evidence shows that TAA helped boost workers’ earnings3 and that the wage insurance component was highly cost-effective, with benefits exceeding the costs even under conservative assumptions.4 Importantly, the wage insurance component sped up the return to work, without getting workers stuck in lower-paying jobs. Indeed, those workers who benefited from the wage insurance returned to work faster, but saw no decrease in earnings in the long term compared to workers who did not benefit from wage insurance.

A natural question is why AI-related job loss should be singled out for special treatment, given that all displaced workers can benefit from such support. The rationale is to sustain social acceptance of AI’s broad benefits by compensating those who bear concentrated losses. Just as the TAA was conceived as compensation to workers for the policy decision to promote trade liberalization, AI-AI can be seen as compensation for the policy decision to encourage rapid AI deployment and remove regulatory barriers, as officially articulated in US policy by “Winning the Race: America’s AI Action Plan.”5

When implementing AI-AI, one may be concerned that it will be difficult to identify job losses that are due to AI. It certainly will not be simple, but the precedent of the TAA program demonstrates that it is possible to establish appropriate procedures. To determine whether a worker lost their job due to trade, the worker’s TAA petition was assigned to case investigators tasked with determining whether layoffs were linked to (1) a direct reduction in sales from import competition, (2) a shift in production to outside the US, or (3) being an upstream supplier or downstream client of firms affected by (1) or (2). This is an instructive example, because it covers not only workers who are at firms that are negatively affected by imports or who outsource, but also workers at other firms who are indirectly affected. One could adapt this process to identify AI-related job loss, for example, by flagging cases where mass layoffs in AI-exposed occupations follow the adoption of new AI-powered software. As with TAA, the outcome (layoffs) is clear, while the challenge lies in attributing the cause; in both cases, investigators rely on contextual evidence to make that link. AI itself could also play a role by supporting investigators with data-driven methods to assess whether observed layoffs are plausibly linked to AI adoption.

“As with TAA, the outcome (layoffs) is clear, while the challenge lies in attributing the cause; in both cases, investigators rely on contextual evidence to make that link.”

The AI-AI can help workers transition more smoothly away from jobs negatively affected by AI and toward new jobs, while minimizing income losses. Prior policy experience suggests such a program is feasible and cost-effective for the American taxpayer.

Scalable income support: The Digital Dividend

A Digital Dividend could help smooth the transition for workers and ensure that everyone gains from AI and the digital economy, even in a bad-case scenario where AI leads to massive job loss and little job creation (for a discussion of scenarios for employment in the time of AI, see Section III). The dividend could be financed by a small proportional tax6 on the digital economy (including AI and digital advertisement), as this sector is likely to benefit the most from AI deployment. Such a tax promotes a more gradual deployment of AI, easing costs to workers as they slowly transition to new jobs.7 The tax revenue would be put into a Digital Fund, which would be invested in a diversified portfolio, and the dividends would go to all citizens. One could

“The dividend could be financed by a small proportional tax on the digital economy (including AI and digital advertisement), as this sector is likely to benefit the most from AI deployment.”

envision the baseline tax rate being zero at first, and then increasing over time if the AI-AI program shows that job losses due to AI are pervasive and lead to long-term unemployment. Thus, the initial levy is deliberately minimal so as not to burden the digital sector and to preserve innovation incentives.

To sum up, the Digital Dividend has two components:

1. A proportional tax on the digital economy: small at first, but increasing if AI-related unemployment becomes widespread.

2. Digital Fund dividends that go to all citizens: benefits increase with AI-related job loss.

Perhaps surprisingly, even the CEOs of AI companies have at times floated the idea of automation taxes or a universal/basic income to protect workers in case of automation. Bill Gates, cofounder of Microsoft, proposed in 2017 that governments should tax companies’ use of robots as a way to slow automation.8 In 2021, Sam Altman, of OpenAI, floated the idea of a universal dividend financed by a tax on large companies and on land, which would be invested in an American Equity Fund.9 In 2024, Elon Musk, of xAI, predicted that, as AI deployment progresses, we will have no jobs, but a universal high income.10 And in 2025, Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, suggested a “token tax” of 3% on the revenue of AI companies.11

There are actual precedents for policies like the Digital Dividend. For example, in the US, the Alaska Permanent Fund has the same two components as the Digital Dividend. The Alaska Permanent Fund is financed by a tax on Alaska’s oil resources and provides a dividend to all Alaskans. For the tax component of the Digital Dividend, an analogy can be found in the Airport and Airway Trust Fund, which draws revenue from a 7.5% excise tax on airline fares to finance the US aviation system, including the Federal Aviation Administration.

The dependence of benefits on economic conditions is also not a new feature. The US unemployment insurance system automatically triggers longer unemployment benefits when the state unemployment rate reaches certain thresholds.12

The Digital Dividend has two rationales. First, the tax component promotes a more gradual deployment of AI: The tax will be borne partially by the digital sector and partially by the buyers of digital technologies, as individuals and companies that adopt AI will have to pay higher prices. Second, the dividend component provides extra income to workers. In the early stages of AI deployment, the first rationale dominates, while the second rationale can become more important later if the bad-case job scarcity scenario materializes.

The first rationale for the Digital Dividend is to encourage a more gradual introduction of AI technologies through a tax. A more gradual deployment of AI can be justified not only by redistributive arguments, but also by appealing to efficiency. From a redistributive standpoint, the tax component helps protect the losers from automation by slowing down automation, which props up their market wages, a form of pre-distribution.13 From an efficiency perspective, the tax helps automating firms internalize a pecuniary externality in the face of incomplete markets: Automation leads to wage declines (the pecuniary externality), and workers are credit constrained (the market imperfection) and therefore cannot fully insure themselves against the wage loss by financing a smooth transition to their next job.14

“The Digital Dividend acts as a universal basic income, and accordingly its focus shifts primarily to financing benefits rather than slowing AI deployment. If the job losses from AI turn out to be large, the triggering of a higher Digital Dividend benefit would be helpful not only to workers but to the economy as a whole.”

The second rationale for the Digital Dividend is to offer a supplemental income benefit to everyone. How valuable such income is depends on the impact of AI on the labor market, which can span different scenarios, as summarized in Table 3 in Section III. If the economy adapts to AI so that employment and wages eventually recover (the good-case or intermediate-case scenario in Table 3), supplemental income may not be needed and the tax may be eventually reduced. If high unemployment becomes durable and pervasive as in the bad-case scenario, we could consider increasing the tax rate, broadening the tax base beyond the digital sector, and increasing tax progressivity. This would increase revenue and help finance a higher level of dividend income with more redistribution. In this bad-case scenario and at later stages of AI deployment, the Digital Dividend acts as a universal basic income, and accordingly its focus shifts primarily to financing benefits rather than slowing AI deployment.

If the job losses from AI turn out to be large, the triggering of a higher Digital Dividend benefit would be helpful not only to workers but to the economy as a whole. Indeed, the key reason why unconditional cash transfers have a more positive employment effect at the macro level than at the individual level is the stimulus effect. When there’s more cash in people’s pockets that is spent on local businesses, these businesses end up needing more workers. Now, if you imagine that AI job losses are large and pervasive, this stimulus effect is likely to be particularly large, because there are a lot of consumers willing to spend, and the AI transformation is likely to yield a lot of products that people would want to buy.

You might, however, be concerned that this cash benefit would discourage work (for more details on this, see Section III). But because the dividend is unconditional, it does not penalize people for working: The unemployed do not lose the money if they go back to work. In that sense, the benefit does not distort the choice between working and not working. At the same time, such unconditional cash has an income effect: Because people are less poor, they are less likely to rush and take the first available job, no matter how bad it is. At the macro level, the transfer puts more cash in the hands of consumers and thus can help create more and better jobs. Empirical evidence supports both points: An unconditional cash transfer has a small negative effect on work when considered at the individual level,15 but it has zero or positive effects on employment at the macro level.16

“An unconditional cash transfer has a small negative effect on work when considered at the individual level, but it has zero or positive effects on employment at the macro level.”

Even if the cash benefit does not increase unemployment, one may be concerned that such an unconditional cash transfer would increase inflation, negating its benefits. However, experiments with large cash transfers in developing countries show that even large and widely distributed cash transfers typically have little to no effect on inflation,17 and there is also no statistically significant effect of the Alaska Permanent Fund on Alaskan inflation.18

While the Digital Dividend would help people in the face of mass unemployment, cash would likely not be enough. In our culture, people lose a sense of meaning when they are out of work, and unemployment can literally kill people.19 So, we will likely also need to imagine new policies that encourage people to engage socially and participate in civic life. If AI were to render our current notion of market work obsolete, we would have to foster and develop other activities that provide the nonmonetary goods of work as theorized by Gheaus and Herzog,20 i.e., attaining excellence, making a social contribution, experiencing community, and gaining social recognition.

The Digital Dividend is a scalable solution to address the potential for mass unemployment resulting from AI. Today, the tax and the dividend would be very small, perhaps even zero, but if AI leads to significantly lower employment, we have a policy that can kick in rapidly and start providing everyone with an unconditional cushion of cash. Under mass unemployment, this policy is needed because unemployment insurance does not cover the long-term unemployed, gig workers, the self-employed, or people who have insufficient work experience. In particular, young people entering the labor market in that era of mass unemployment would have trouble becoming eligible for unemployment benefits, and therefore could also not benefit from AI-AI. This is why we need a plan B like the Digital Dividend to provide broader support in the event of AI-driven mass unemployment.

Table 1 summarizes and compares the AI Adjustment Insurance and the Digital Dividend policies.

III. Why We Support Jobless Workers and Why Policies Evolve in the Age of AI

Why we support jobless workers

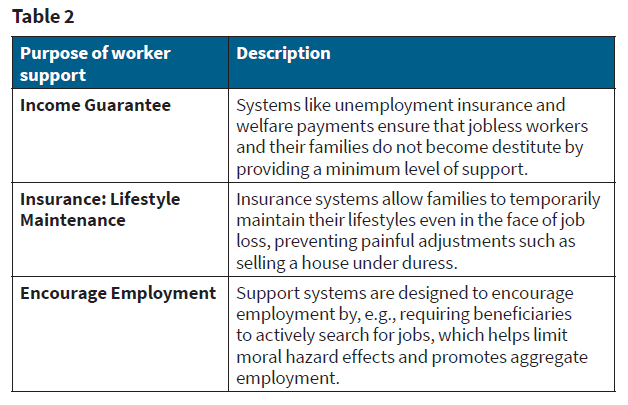

Most people are working to support themselves and their families. When workers lose their jobs, their families’ livelihoods are at stake. If they stay unemployed for too long, they might lose their house or go hungry. To avoid such dire outcomes, we have created systems of support such as unemployment insurance and welfare payments. These systems ensure that jobless workers and their families do not become destitute. By providing a minimum level of support to workers, they act as income floors, or income guarantees.

For middle-class families, however, a mere income guarantee is not enough to provide a sense of safety. Even if job loss doesn’t immediately lead to destitution, a large drop in income would force these families to make painful adjustments, such as selling their house. This is why we also provide workers with insurance that helps them largely maintain their lifestyles, even in the face of job loss.

Importantly, these support systems are conditional on workers staying unemployed or low income; after all, these systems were put in place to help people who lose their jobs. Unfortunately, the side effect is that these systems can encourage workers to stay unemployed longer to continue collecting benefits, potentially leading to long-term dependency. This is the so-called “moral hazard” effect of these benefits. Generous worker support systems may lead to disemployment effects.

“A system of unconditional income support, where everyone receives an income guarantee, no matter what, would avoid creating incentives for people to remain unemployed or poor in order to collect benefits.”

A system of unconditional income support, where everyone receives an income guarantee, no matter what, would avoid creating incentives for people to remain unemployed or poor in order to collect benefits. Empirical research shows that such unconditional cash transfers, when deployed at scale, do not decrease employment.21 However, such a system is much more expensive, since everyone receives the income guarantee, whether unemployed or not, whether rich or poor. This is a key reason why we have opted for a more targeted system that conditions benefit receipt on unemployment or low income, even as this conditionality can discourage workers from taking a new job.

In practice, research shows that, yes, more generous unemployment benefits tend to increase the duration of unemployment,22 as predicted by moral hazard effects. But these effects can become vanishingly small during high unemployment periods, when jobs are scarce and workers face significant difficulties in finding a new job, as we saw during the Great Recession of 2008 or during the 2020 COVID-19 recession.23

Support systems for jobless workers are often explicitly designed to encourage employment, for example, by requiring unemployment insurance beneficiaries to actively search for jobs. These features help limit moral hazard effects and promote employment.

Why do we want to promote employment? One reason is fiscal: to limit the total cost of benefits, and to increase tax revenues, as employed workers pay higher taxes than the unemployed. But there are also other reasons. Some people believe work has intrinsic value, providing meaning and dignity.

To sum up, we have systems in place that provide income guarantees and insurance to help workers who lose their jobs support themselves and their families, and to promote employment (see summary in Table 2). But will these systems be enough to deal with the job loss that AI is likely to bring about?

Worker support policies in the age of AI: What’s new?

As a general-purpose technology, AI has the potential to be used across many different domains and can spur additional innovations and improve over time. As it is adopted across economic sectors, a general-purpose technology will reorganize jobs across these sectors. Some job loss is largely unavoidable as jobs are restructured to better fit with the new technology. We need to be prepared to support the workers who become unemployed, even if only temporarily.

Historically, we have faced several such structural shocks, where the labor market was reorganized in the wake of the adoption of a new general-purpose technology. A prime example is electricity, which thoroughly reorganized the US economy at the beginning of the 20th century. As more and more regions of the US became electrified, the structure of the labor market was transformed, with fewer jobs in agriculture and an increasing number of industrial jobs. In other terms, electricity facilitated the so-called “structural transformation” of the economy, with workers moving from the primary to the secondary sector.24

“Importantly, even when new jobs are created, as was the case with electrification, workers who become unemployed typically suffer significant losses.”

Importantly, even when new jobs are created, as was the case with electrification, workers who become unemployed typically suffer significant losses. Looking at more recent evidence, workers who are displaced as a result of plant closures and mass layoffs suffer significant and durable earnings losses of 15% to 25%.25 The transition is usually not smooth for displaced workers, highlighting the importance of having a well-designed support system in place

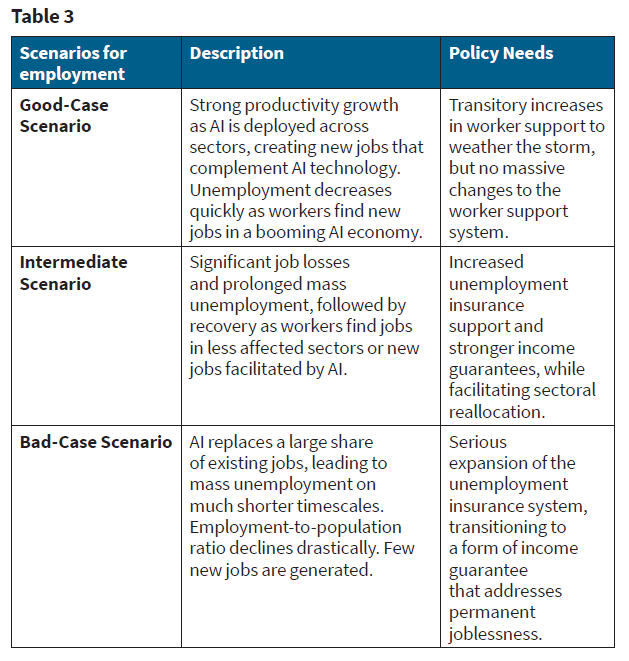

But how large and durable will the job losses from AI be? There are two possible ends of a spectrum: a good-case scenario and a bad-case scenario. In the good-case scenario for employment, AI is deployed across sectors, productivity increases, and new jobs are created that complement the AI technology. This will not, however, prevent job losses for workers whose jobs are replaced by AI, and research shows that automation via robots26 or AI technologies27 has indeed precipitated a reduction in employment in exposed sectors. But, importantly, in this good-case scenario, we can expect unemployment to quickly decrease as workers find new jobs in a booming AI economy. In this scenario, we may need some transitory increases in worker support to weather the storm, but the technology shock would not necessitate massive changes to the worker support system.

In the bad-case scenario, AI and robots replace a large share of existing jobs, but there are few new jobs generated. AI may diffuse faster than other technologies like electricity, because there is less necessary infrastructure for deployment. We already have computers, data centers, and high-speed internet, while electrification necessitated the construction of new electric plants and transmission lines. The diffusion of AI could thus lead to mass unemployment on much shorter timescales than was ever the case for prior general-purpose technologies. In this bad-case scenario, we would likely need to seriously beef up the unemployment insurance system. Such an expansion would not generate significant disemployment effects, as there are simply no jobs for workers to take, so there is limited opportunity for moral hazard effects. If it is anticipated that workers will face permanent unemployment, it is crucial to shift from an unemployment insurance system that assumes employment as the standard condition, toward implementing a form of income guarantee for all.

“If it is anticipated that workers will face permanent unemployment, it is crucial to shift from an unemployment insurance system that assumes employment as the standard condition, toward implementing a form of income guarantee for all.”

There could also be an intermediate scenario with significant job losses and prolonged mass unemployment, followed by recovery as workers find jobs in less affected sectors or in brand-new jobs facilitated by AI. This scenario would also necessitate increased unemployment insurance support, as well as potentially stronger income guarantees. However, if we can reasonably expect employment to recover, we need to be more mindful of how the beefed-up support systems we put in place for jobless workers may discourage sectoral reallocation, i.e., workers’ transition away from affected sectors and into new jobs. We need to think about how we can facilitate this reallocation while providing ample insurance to workers who are displaced by AI.

Table 3 summarizes these different scenarios. It is important to remember that the labels “good” or “bad” refer to employment, with the bad-case scenario corresponding to high employment losses. The labels do not refer to people’s well-being: It is possible that, with the right worker support system, the “bad” scenario for employment is the “good” scenario for people’s well-being, as people can benefit from high incomes and more leisure time.

IV. Conclusion

The development of AI presents unique opportunities for economic development, but also significant risks of mass unemployment. To ensure that workers benefit from AI, we should consider a flexible system of worker support that insures workers against AI-induced job losses today, promotes the transition of workers to new jobs, and provides broad unconditional income support in the event of mass unemployment. The AI Adjustment Insurance (AI-AI) is a targeted program that supports workers who have lost their jobs to AI, combining income support, training, and wage insurance. The program also allows us to track job losses due to AI. The Digital Dividend starts small, and the tax that finances it promotes a gradual deployment of AI. The Digital Dividend can be phased out if the labor market adjusts well to AI, or increased over time to provide unconditional income support to all in the event of permanent AI-driven mass unemployment and job scarcity. This flexible system supports workers across the range of possible impacts of AI on the labor market.

“To ensure that workers benefit from AI, we should consider a flexible system of worker support that insures workers against AI-induced job losses today, promotes the transition of workers to new jobs, and provides broad unconditional income support in the event of mass unemployment.”

1. Ioana Marinescu, “The General Equilibrium Impacts of Unemployment Insurance: Evidence from a Large Online Job Board,” Journal of Public Economics 150 (June 2017): 14–29, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2017.02.012.

2. David Card, Jochen Kluve, and Andrea Weber, “Active Labour Market Policy Evaluations: A Meta-Analysis,” The Economic Journal 120, no. 548 (2010): F452–F477, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2010.02387.x.

3. Benjamin Hyman, “Can Displaced Labor Be Retrained? Evidence from Quasi-Random Assignment to Trade Adjustment Assistance,” SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 3155386 (January 10, 2018), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3155386.

4. Benjamin Hyman, Brian Kovak, and Adam Leive, “Wage Insurance for Displaced Workers,” Working Paper No. 32464, (National Bureau of Economic Research, May 2024), https://doi.org/10.3386/w32464.

5. Executive Office of the President, Winning the Race: America’s AI Action Plan (The White House, 2025), https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Americas-AI-Action-Plan.pdf.

6. Unlike the corporate income tax, which applies roughly to profits, the Digital Dividend would be levied on revenues (or sales or value added), meaning it can raise more revenue at a given rate.

7. Nils Haakon Lehr and Pascual Restrepo, “Optimal Gradualism,” Working Paper No. 30755 (National Bureau of Economic Research, December 2022), https://doi.org/10.3386/w30755; Joao Guerreiro, Sergio Rebelo, and Pedro Teles, “Should Robots Be Taxed?” The Review of Economic Studies 89, no. 1 (2022): 279–311, https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdab019; Martin Beraja and Nathan Zorzi, “Inefficient Automation,” The Review of Economic Studies 92, no. 1 (2015): 69–96, https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdae019.

8. Kevin J. Delany, “Bill Gates: This is Why We Should Tax Robots,” World Economic Forum, February 10, 2017, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2017/02/bill-gates-this-is-why-we-should-tax-robots/.

9. Sam Altman, “Moore’s Law for Everything,” Sam Altman (blog), March 16, 2021, https://moores.samaltman.com.

10. John Csiszar, “Elon Musk Says Universal Income is Inevitable: Why He Thinks That’s a Bad Thing,” Nasdaq, March 27, 2025, https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/elon-musk-says-universal-income-inevitable-why-he-thinks-thats-bad-thing.

11. Jim VandeHei and Mike Allen, “Behind the Curtain: A White-Collar Bloodbath,” Axios, May 28, 2025, https://www.axios.com/2025/05/28/ai-jobs-white-collar-unemployment-anthropic.

12. Marinescu, “The General Equilibrium Impacts of Unemployment Insurance.”

13. Lehr and Restrepo, “Optimal Gradualism”; Guerreiro, Rebelo, and Teles, “Should Robots Be Taxed?”; Arnaud Costinot and Iván Werning, “Robots, Trade, and Luddism: A Sufficient Statistic Approach to Optimal Technology Regulation,” Review of Economic Studies 90, no. 5 (2023): 2261–91, https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdac076.

14. Beraja and Zorzi, “Inefficient Automation.”

15. Ioana Marinescu, “No Strings Attached: The Behavioral Effects of U.S. Unconditional Cash Transfer Programs,” Working Paper No. 24337 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2018), https://doi.org/10.3386/w24337; Eva Vivalt, Elizabeth Rhodes, Alexander Bartik, David Broockman, Patrick Krause, and Sarah Miller, “The Employment Effects of a Guaranteed Income: Experimental Evidence from Two U.S. States,” Working Paper No. 32719 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2024), https://doi.org/10.3386/w32719.

16. Damon Jones and Ioana Marinescu, “The Labor Market Impacts of Universal and Permanent Cash Transfers: Evidence from the Alaska Permanent Fund,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 14, no. 2 (May 2022): 315–40, https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20190299; Dennis Egger, Johannes Haushofer, Edward Miguel, Paul Niehaus, and Michael Walker, “General Equilibrium Effects of Cash Transfers: Experimental Evidence from Kenya,” Econometrica 90, no. 6 (2022): 2603–43, https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA17945.

17. Egger et al., “General Equilibrium Effects of Cash Transfers.”

18. Damon Jones and Ioana Marinescu, “Universal Cash Transfers and Inflation,” National Tax Journal 75, no. 3 (2022): 627—53, https://doi.org/10.1086/720770.

19. Daniel Sullivan and Till von Wachter, “Job Displacement and Mortality: An Analysis Using Administrative Data,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 124, no. 3 (2009): 1265–306, https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2009.124.3.1265.

20. Anca Gheaus and Lisa Herzog, “The Goods of Work (Other Than Money!),” Journal of Social Philosophy 47, no. 1 (2016): 70–89, https://doi.org/10.1111/josp.12140.

21. Egger et al., “General Equilibrium Effects of Cash Transfers”; Jones and Marinescu, “The Labor Market Impacts of Universal and Permanent Cash Transfers.”

22. Ioana Marinescu and Daphné Skandalis, “Unemployment Insurance and Job Search Behavior,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 136, no. 2 (2021): 887–931, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjaa037.

23. Marinescu, “The General Equilibrium Impacts of Unemployment Insurance”; Ioana Marinescu, Daphné Skandalis, and Daniel Zhao, “The Impact of the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation on Job Search and Vacancy Creation,” Journal of Public Economics 200 (August 2021): 104471, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2021.104471.

24. Paul Gaggl, Rowena Gray, Ioana Marinescu, and Miguel Morin, “Does Electricity Drive Structural Transformation? Evidence from the United States,” Labour Economics 68 (January 2021): 101944, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2020.101944.

25. Louis S. Jacobson, Robert J. LaLonde, and Daniel G. Sullivan, “Earnings Losses of Displaced Workers,” The American Economic Review 83, no. 4 (1993): 685–709, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2117574; Kenneth A. Couch and Dana W. Placzek, “Earnings Losses of Displaced Workers Revisited,” American Economic Review 100, no. 1 (2010): 572–89, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.1.572.

26. Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, “Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Market,” Journal of Political Economy 128, no. 6 (2020): 2188–244, https://doi.org/10.1086/705716.

27. Menaka Hampole, Dimitris Papanikolaou, Lawrence D.W. Schmidt, and Bryan Seegmiller, “Artificial Intelligence and the Labor Market,” Working Paper No. 33509 (National Bureau of Economic Research, February 2025), https://doi.org/10.3386/w33509.