Titans, Swarms, or Human Renaissance? Technological Revolutions and Policy Lessons for the AI Age

Will transformative AI bring prosperity or disorder? This essay presents a new typology of past technological revolutions—from the Industrial Revolution to the information age—defined by their impact on market structure and labor. Applying this framework to the AI era, the author analyzes four potential futures (Titan’s Dominion, Copilot Empire, Disruption Swarm, and Promethean Fire) and identifies five priorities for steering outcomes toward broad-based prosperity through policies spanning tax, innovation, competition, AI governance, and infrastructure.

Imagine a technology that transforms the production of essential goods. In one place, a workforce that had been indispensable for centuries is suddenly obsolete. The new machines are faster, cheaper, and never tire. Deprived of purpose, the population collapses within a few generations.

Meanwhile, among another group of workers, the same technology creates unprecedented prosperity. Workers initially displaced by the machines eventually find new roles and share in the gains. The bounty of the machines raises living standards to previously unimaginable heights.

You might think I’m describing the mechanization of agriculture. When tractors replaced animal power, the horse population collapsed. At the same time, mechanization made food more plentiful and created new opportunities for farm workers in manufacturing.

The horse metaphor is now a familiar touchstone in the artificial intelligence (AI) debate. Will humans continue to find new work, as we always have? Or will AI grow so capable that humans become the horses?1

But this story is not about horses. It is about the mechanization of textiles in 18th and 19th century Britain. In Manchester, it forged the first great factory city, a thriving industrial middle class, and eventually a rising working class. In colonial Bengal—then a major textile center for the world—it devastated an entire civilization of weavers. The population of Dhaka fell from 200,000 to 50,000.2

Why did one technology—the same technology—that brought desolation to one group bring abundance to another?

Even in Manchester, the benefits of the new technology were at first not widely shared, with the gains concentrated with factory owners. But economic and social adaptation—including government policy changes benefiting workers—gradually helped usher in an era of widening prosperity. Bengal, by contrast, was subject to British colonial rule. Discriminatory British colonial policies protected Britain’s textile industry and cultivated the threat to Bengal’s textiles in the first place, while later inhibiting that society’s ability to adapt to the technological disruption.3

“The key lesson is that the difference lay not solely in the technology itself, but in who controlled it, how it was deployed, and how governments responded.”

The key lesson is that the difference lay not solely in the technology itself, but in who controlled it, how it was deployed, and how governments responded. Understanding these dynamics is more important than ever in the era of AI. Transformative AI aims to surpass human intelligence across multiple fields. How do we prepare for that prospect?

A Typology for Technological Revolutions

To analyze the potential challenges and opportunities raised by transformative AI, it is useful to have a framework to contextualize prior technological revolutions, identify essential attributes, and extract historical lessons that are relevant today.

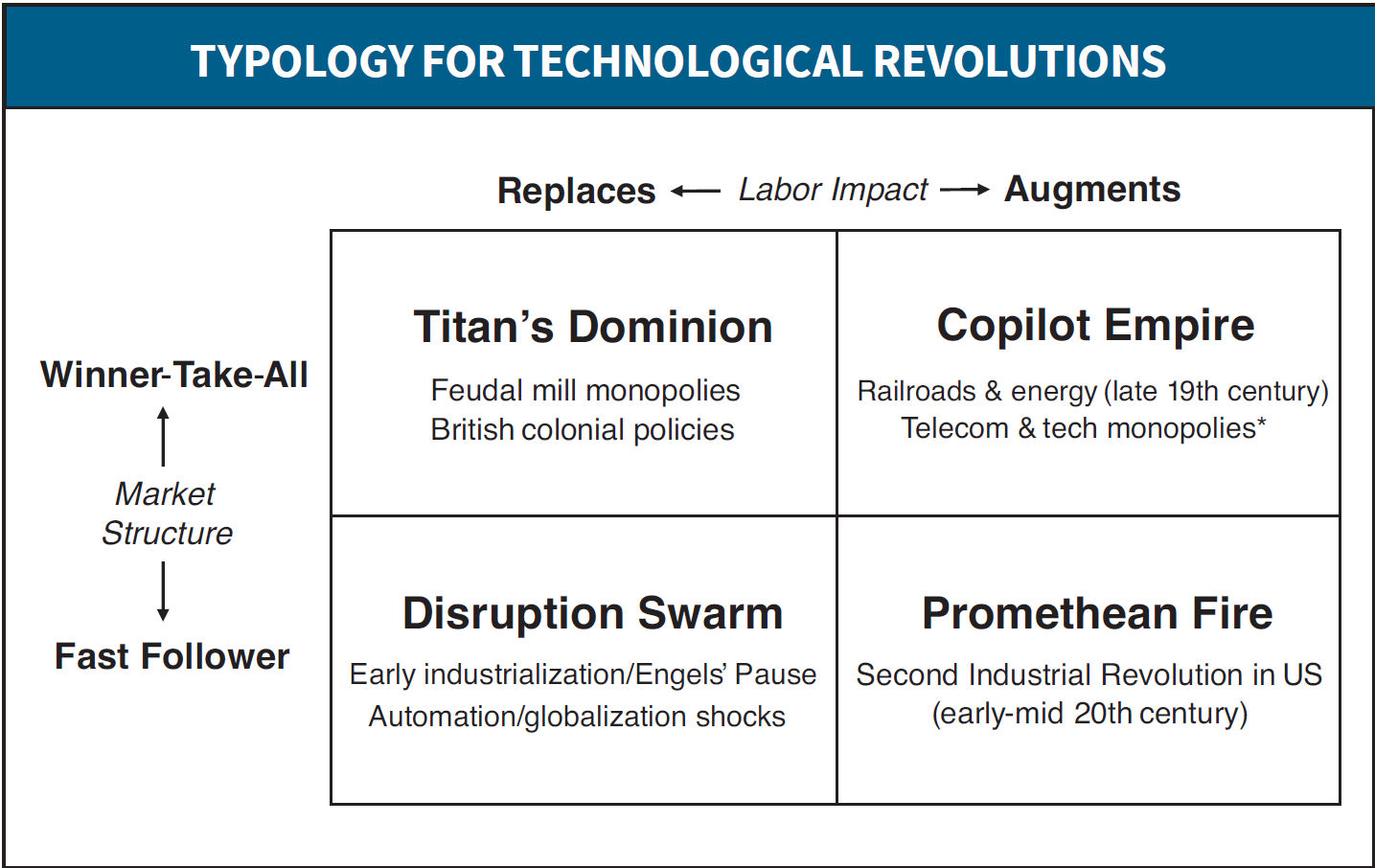

Our typology focuses on two core elements integral to both the economics and the political economy of technological disruptions.

The first attribute is the extent to which a technology displays winner-take-all versus fast-follower dynamics.

A winner-take-all technology is one in which the leading firm tends to capture most or all of the market. Several forces can produce this outcome: (1) powerful scale economies in which upfront capital costs are massive while marginal costs to serve additional customers are low; (2) network effects, where the value of a service increases with the number of users; and (3) first-mover advantages, where the pioneering firm locks in customer loyalty, shapes technical standards, establishes a dominant ecosystem with proprietary technology, or achieves regulatory capture. In the case of AI, data flywheels may be especially important, in which an initial head start in users enables the leading firm to collect more data, build better products, and attract even more users in a reinforcing feedback loop.4

By contrast, a fast-follower scenario is one in which (1) knowledge diffuses rapidly and intellectual property is easy to work around; (2) interoperability is high and switching costs for customers are low; and (3) rapid catch-up and vigorous competition limit pricing power and accelerate commoditization. When fast-follower dynamics predominate, competitive imitation overcomes barriers to entry, and the race shifts to deployment and scaling. Execution, operational proficiency, and the ability to leverage complementary assets become more important to success than initial invention.5

The second attribute is the extent to which a technology exhibits labor-replacing versus labor-augmenting characteristics.6

Technological advances often enable machines to replace human labor in executing certain tasks—whether that means spinning yarn, harvesting grain, or crunching numbers. This makes it possible to produce the same output with fewer workers performing those tasks. When technology enables capital to readily substitute for labor at a lower cost, automation can cause significant job losses or put downward pressure on wages.7

“Historically, even technologies that have been strongly labor-saving in a narrow sense have usually proven to be labor-augmenting in a broader sense.”

Yet historically, even technologies that have been strongly labor-saving in a narrow sense have usually proven to be labor-augmenting in a broader sense. First, such technologies often require new complementary human inputs— additional workers to operate, maintain, and manage the integration of new machines into production processes. Second, the lower cost to produce a given output can increase demand for that output and can make workers who utilize that output more valuable, both of which can increase employment and wages. Finally, at the level of the economy, novel technologies have historically made entirely new industries possible, creating demand for new products and services— and therefore new kinds of work—that previously did not exist. The net effect over time has been to increase demand for labor and raise wages, despite first-order labor-replacing effects.8

Two important caveats are in order. First, “labor” is not monolithic. Technology can have different impacts on different types of workers— high-skilled versus low-skilled, entry-level versus incumbent, men versus women. The average impact of a technological disruption may mask important differences among different categories of workers, replacing some and augmenting others. Second, it can be difficult to predict at the outset whether a particular technology will ultimately be labor-replacing or labor-augmenting. A canonical example is automated teller machines (ATMs), which ended up expanding banking employment by making it cheaper to open branches and serve customers.9

History also suggests that it takes time for the ultimate impact of a technological disruption to be realized. Unlocking the full potential of a technology—especially a general-purpose technology (GPT)—typically requires reorganization of workflows and business processes, acquisition of new worker and manager skills, and other complementary investments. This process of integrating new technologies shapes both competitive dynamics among firms as well as the impact on workers.10

“Unlocking the full potential of a technology— especially a general-purpose technology (GPT)—typically requires reorganization of workflows and business processes, acquisition of new worker and manager skills, and other complementary investments.”

We can use these two axes to create a 2x2 matrix with four different configurations. The upper-left quadrant, in which monopoly power dominates a technology that is massively labor-replacing, is labeled Titan’s Dominion. The upper-right quadrant, in which monopolistic forces are strong alongside a technology that is labor-augmenting in character, is labeled the Copilot Empire. The lower-left quadrant, in which fast-follower dynamics promote the rapid diffusion of a labor-replacing technology, is called the Disruption Swarm. And the lower-right quadrant, where decentralized application of a labor-augmenting technology prevails, is named Promethean Fire.

Applying the Matrix to the Technological Past

History offers examples of humanity’s experiences with each of these quadrants.

Titan’s Dominion

Monopolistic control of a broadly labor-replacing technology is rare in human history, particularly as a market outcome.

“It was not the inherent attributes of the technology alone that led to oppressive outcomes, but rather the interaction of that technology with the prevailing political system and the interests that system was organized serve.”

There are historical examples of a political order imposing such a technological monopoly by decree. In the medieval period, feudal lords enforced monopolies on water mills, a technology that enabled grain to be ground with vastly less human labor than hand-milling. Private milling was banned, even in the home. Peasants were compelled to pay high fees to use the mills, allowing feudal lords to appropriate the economic gains. Feudal rules controlling prices and labor services inhibited channels through which augmentation dynamics might have otherwise operated and shared productivity gains more widely.11

Discriminatory colonial policies also fit the definition of Titan’s Dominion, where the technological monopoly of the imperial power is supported and sustained by deliberate policies that restrict who benefits. The opening vignette of Bengal’s collapse as a textile hub is an example: British imperial policy and domestic politics supported the development of manufacturing at home and of raw-material production in the colonies, while stifling the ability of colonial societies to adapt to rapid change.12

These examples illustrate the potential for exploitative alliances between labor-replacing technology and political elites. In these instances, it was not the inherent attributes of the technology alone that led to oppressive outcomes, but rather the interaction of that technology with the prevailing political system and the interests that system was organized to serve.

Copilot Empire

Economic history has many more examples of concentrated control of technologies that augmented human labor. Indeed, it has been a pervasive feature of modern economic development.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the physical backbone of the growing US economy was dominated by monopolies. From communications to railroads to electricity distribution to oil refining, concentrated business interests were dominant, driven in large part by the factors described above for winner-take-all technologies, especially large fixed-cost capital investments and strong network effects.13

These innovations proved to be massively catalytic and laboraugmenting for the broad American economy, facilitating commerce and connecting markets, powering a wide range of new industries, while expanding opportunity and raising incomes for workers. At the same time, these concentrated interests also led to abuses. Powerful monopolies exploited and threatened workers, leveraged market power to coerce captive customers and crush potential rivals, and forged alliances with politicians to sustain their dominance.14

Social and political responses played a critical role in managing these pressures. The excesses of the monopolies produced landmark antitrust legislation, jurisprudence, and regulatory innovation that expanded federal authority to rein in monopoly power, while a rising organized-labor movement pressed the interests of workers in this era of rapid change.15

“From the telecommunications monopoly of AT&T, the mainframe dominance of IBM, the operating system dominance of Microsoft, and the search dominance of Google, powerful technologies with winner-take-all dynamics reshaped and facilitated the expansion of the modern US economy, while creating new antitrust challenges.”

These institutions proved important in the latter half of the 20th century and in the 21st century, as concentrated business interests in core technologies have been a central feature of post-World War II American economic growth. From the telecommunications monopoly of AT&T, the mainframe dominance of IBM, the operating system dominance of Microsoft, and the search dominance of Google, powerful technologies with winnertake- all dynamics reshaped and facilitated the expansion of the modern US economy, while creating new antitrust challenges.16

Overall living standards and employment have risen during this period. But there is an asterisk to this Copilot Empire. To be sure, many workers have benefited from the diffusion of computer and communications technologies. However, recent decades have seen a sharp divide in the labor market. Wages for high-skilled workers have surged, while wages for lower-skilled workers have stagnated or fallen. Technology is identified as a key driver of this polarization, highlighting the potential for technological disruptions with centralized control to augment some workers (emblematic of the Copilot Empire) and replace others (with hints of Titan’s Dominion).17

Disruption Swarm

Instances of decentralized technology diffusion disrupting particular sectors are common. What distinguishes a Disruption Swarm is the pervasiveness of the effect on a broad category of workers over a sustained period of time. While technology has historically been broadly labor-augmenting in nature—raising both employment and wages for the overall economy over time—there are examples where this has not held true over meaningful time horizons or for significant swaths of workers.

Perhaps the most instructive example is the early phase of the Industrial Revolution in Britain from the late 18th to mid-19th century. During this period, new technologies like the power loom diffused rapidly, and new factories replaced the cottage-based putting-out system, pushing many handloom weavers out of work.

Although productivity soared during this period of time, it was capital owners that captured most of the profits. Wages for the working class stagnated for several decades in the first half of 19th century Britain, and health metrics also deteriorated. This period—known as “Engels’ Pause”—shows that higher productivity growth does not necessarily translate into higher wage growth, or at least that the lag can last more than a generation.18

What ended Engels’ Pause? It was a constellation of economic, technological, policy, and societal factors. Capital accumulation and the arrival of steam power increased demand for workers with higher levels of human capital to operate complex machinery. Meanwhile, new technologies boosted labor demand for unskilled and semiskilled workers elsewhere in the economy, particularly in railway construction.19

On the policy side, repeal of the Corn Laws eliminated tariffs on imported grain, which reduced food prices and boosted real wages. In addition, legal changes such as the Factory Acts of the 1830s placed limits on child and female labor, thus constraining the supply of unskilled labor, while early labor organization into trade unions created collective bargaining power to advocate for worker interests. Public health interventions improved health outcomes, while expanding education deepened human capital. Combined, these developments produced rising living standards in the second half of the 19th century.20

A more recent example of the Disruption Swarm is the transformation of manufacturing in advanced economies in recent decades. Declining manufacturing employment and stagnant wages, particularly for lower-skilled workers, have coincided with a period of automation and globalization. Economists debate the general-equilibrium effects on the well-being of workers overall, and whether to attribute primary causality to technology or trade. But it is clear that particular geographical areas reliant on manufacturing experienced employment dislocation, declining economic prospects, and deteriorating social indicators.21

Promethean Fire

Decentralized, rapidly diffused technologies that augment human capabilities have been some of the most potent tools for raising human welfare.

The Second Industrial Revolution—especially from the early to mid-20th century in the United States—included multiple technologies that fit these criteria. Indoor plumbing and sanitation dramatically reduced disease and improved health. Mass-produced consumer appliances reduced household work and enabled more women to work outside the home. Innovations in chemistry produced a modern chemical industry that revolutionized agriculture with new fertilizers, manufacturing with new industrial processes, and health through pharmaceuticals.22

Applications of the internal-combustion engine and electrical machinery technology were particularly widely distributed and transformative. Automobiles, trucks, tractors, and heavy construction equipment boosted productivity, enabled new kinds of economic activity, and facilitated distribution and market linkages. Electrification of factories not only made possible new kinds of machines but enabled the reorganization of assembly lines, freeing workflows from the constraints of fixed belts and shafts from the era of steam power.23

A defining characteristic of these innovations was that they complemented human labor both directly (the machines needed human operators) and indirectly (via second-order effects that created demand for new products and services). In the latter category, higher output-per-worker that reduced costs of production meant lower prices for the final products, which led to higher final demand, more demand for workers in that industry, more demand for workers creating inputs to that industry, and more demand for workers in industries facilitated by widespread availability of the output of that industry.24

“A defining characteristic of these innovations was that they complemented human labor both directly (the machines needed human operators) and indirectly (via second-order effects that created demand for new products and services).”

The US auto industry—where employment surged in the first half of the 20th century even as productivity rose—illustrates this phenomenon and its knock-on effects across the economy. Lower prices for motor vehicles meant consumers and businesses bought more of them. This in turn created entirely new jobs both in related industries (steel, machine tools, rubber, gas stations, hotels and hospitality, auto repair) and in unrelated industries (by making the transportation of goods and people cheaper).25

Public investments played a key role in realizing the potential of Promethean Fire. First, investments that the United States made in public education starting in the 19th century prepared workers to take advantage of new types of employment that required technical skills. Second, investments in physical infrastructure to spread electrification and expand the road network were instrumental in providing the platform for businesses, workers, and households to leverage.26

Which Quadrant Is Our AI Future?

Situating transformative AI within this matrix framework requires answering two questions. First, to what extent will transformative AI be a winner-take-all versus fast-follower technology? Second, to what extent will it be labor-replacing versus labor-augmenting? We cannot answer these questions definitively. But we can review the evidence on how AI has developed in recent years, as well as extract insights from technological revolutions of the past.

There are three key reasons to think that transformative AI may display winner-take-all dynamics. First, the training of frontier AI models requires massive upfront fixed costs, with initial training for a new model running into the hundreds of millions of dollars and the underlying computational infrastructure to train and serve models running into the hundreds of billions of dollars. Second, several of the leading technologies (OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google’s Gemini, and Anthropic’s Claude) are proprietary. Third, the potential remains substantial for a vigorous positive feedback loop between the number of users and the quality of the product. All of these factors create formidable barriers to new entrants and create strong first-mover advantages.27

While these factors underscore the potential of AI to become winner-take-all in the future, the current situation also contains multiple elements of a fast-follower dynamic.

Although OpenAI enjoys the largest market share thanks to the massively successful launch of ChatGPT in late 2022, its competitors are not out of the game, especially in the enterprise sector. Moreover, OpenAI’s lead in market share has so far not translated into a runaway data flywheel dynamic in product quality, with recent technical performance leaderboards remaining competitive and highly fluid. Major deep-pocketed corporations like Google, Microsoft, and Meta appear determined to make massive multibillion dollar investments in AI because they view losing the AI race as a potential existential threat to their core businesses. Finally, much less expensive open-source models have the potential to offer performance that is slightly behind the frontier but at a fraction of the cost, as demonstrated by the dramatic entry of China’s DeepSeek in early 2025.28

“The cost of training frontier models and delivering inference at scale could become increasingly exorbitant and difficult to recover, putting it out of reach of all but a few giant corporations.”

One possibility is that the current intense competition gives way to consolidation in the years ahead, especially if the path to transformative AI requires relentlessly increasing expenditure of the kind we have seen with large language models (LLMs). This could be the case if “scaling laws” continue to prevail (with capabilities improving in predictable, power-law fashion as compute, data, and model size increase) while gains from algorithmic and systems efficiency slow or plateau (making it difficult to replicate cost-efficiency innovations like DeepSeek). In that scenario, the cost of training frontier models and delivering inference at scale could become increasingly exorbitant and difficult to recover, putting it out of reach of all but a few giant corporations. This pattern would be reminiscent of the railways buildout in the United States in the 19th century, which was initially highly competitive but then consolidated.29

The other possibility is that no single company sustains a durable dominant position and the “cost of intelligence” continues to plunge. That could prevail because the marginal returns to brute-force parameter scaling diminish while training and serving efficiency keep improving; multiple industry giants continue making massive investments at the frontier to avoid ceding an edge to competitors; or “good enough” intelligence (as opposed to frontier) ends up being the best fit for most applications in the economy. Some researchers argue that economically potent AI may involve a suite of AI agents that leverage specialized and cheaper small language models (SLMs), rather than relying solely on a hyperscaled monolithic LLM. All this could add up to a competitive fast-follower world in which the unit cost of intelligence keeps falling, and the innovative edge moves to the application layer—reminiscent of how electricity generation became a commodity, spawning massive innovation in the end-uses of electricity in machinery.30

“Some researchers argue that economically potent AI may involve a suite of AI agents that leverage specialized and cheaper small language models (SLMs), rather than relying solely on a hyperscaled monolithic LLM.”

It is similarly difficult to have a conclusive answer to whether transformative AI technologies will be labor-replacing or laboraugmenting.

While history suggests that technology has been labor-augmenting in the long run, there are reasons to believe that the disruption this time could be more severe. The breadth of human capabilities that transformative AI may replicate could be unprecedented, creating an absolute advantage across so many tasks that demand for human labor at prevailing wages collapses. The speed with which AI capabilities are expanding is also unprecedented, giving the economy and labor market less time to adjust, raising the chances of dislocation. Finally, there is a risk that corporate CEOs view worker replacement as the most straightforward way to realize financial returns on AI investments, and that AI providers may find worker replacement the most straightforward way to monetize their technology.31

There are preliminary indications that AI systems are negatively impacting employment in certain segments of the labor market. A large-scale analysis of private payroll data finds that employment for young workers has declined in AI-exposed occupations, especially in jobs where AI automates tasks. This is consistent with anecdotes from software development, law, professional services, and other whitecollar professions of employers either experimenting with or deploying AI systems for work done by entry-level employees. Some analysts speculate that businesses could use the next recession to downsize their workforces and expand the use of technological replacements, similar to the “jobless recoveries” of previous recessions.32

At the same time, compelling early evidence also illustrates the strong labor-augmenting potential of AI systems. While empirical work is nascent, studies have begun to identify substantial increases in worker productivity via augmentation with AI. In some sectors it is less-experienced workers whose productivity increased the most (customer service call centers, software development, writing, legal services, and management consulting). In others, it is experienced workers who excelled in leveraging AI’s capabilities (accounting, entrepreneurship).33

Even advanced AI systems may lack the capability to replace certain human attributes—like empathy, personal connection, physical presence, judgment, imagination, and leadership—that are integral components of many jobs. This points to the potential for complementarities between human and transformative AI capabilities in the workplace.34

“Even advanced AI systems may lack the capability to replace certain human attributes— like empathy, personal connection, physical presence, judgment, imagination, and leadership—that are integral components of many jobs.”

All of this suggests a nuanced and complex picture of how AI systems may interact with human workers in the future. The degree of replacement versus augmentation may not be uniform. Rather, it may vary according to the needs of different industries, complementarities between human and machine proficiencies in different tasks, the work processes of different organizations, and the readiness of individual workers to utilize AI tools.35

History offers powerful evidence that as the economy evolves to incorporate powerful new technologies, it brings forth constellations of products and services requiring human inputs that were previously unimaginable. But this also takes time. Integrating general-purpose technologies requires organizational adaptation, new business processes, and human capital investments. Uncertainty and institutional inertia mean that there will be lags in implementation and difficulties in realizing and measuring the productivity impacts.36

It is difficult to know ex ante how these realities of human organizations will affect the pace of labor replacement versus augmentation. Will social resistance and organizational inertia slow the pace of worker replacement? Or is automation the “low-hanging fruit” of corporate implementation, while the more sophisticated processes to harness the benefits of augmentation require more patience and longer gestation?

“Will social resistance and organizational inertia slow the pace of worker replacement? Or is automation the “low-hanging fruit” of corporate implementation, while the more sophisticated processes to harness the benefits of augmentation require more patience and longer gestation?”

Meanwhile, a demographic clock is also ticking in the background: Plunging birth rates mean that many parts of the world are moving into a period where the working-age population is poised to decrease markedly, meaning that the labor force will be shrinking in the decades ahead—potentially an offset to a labor-saving bias of transformative AI.37

The bottom line is that the jury is out on which quadrant a transformative AI future will occupy. The discussion above—and experience with previous technological revolutions—makes clear that the answer is not deterministically ordained by the characteristics of the technology alone. Rather, it is shaped by the interaction between technology and human institutions. While the technology constrains the range of possibilities and can bias the system toward certain outcomes, the journey and ultimate destination are forged by the choices made by businesses, workers, civil society, and government.

Complicating Factors: Misuse, Misalignment, and Global Competition

Several complicating factors about transformative AI are worth noting. Each merits an essay of its own and a full treatment is beyond the scope of this piece. But they are relevant to consideration of the promise and peril of various quadrants, as well as policy implications.

While all technologies have the capacity to be used for harmful purposes, the prospect of transformative AI could put especially powerful capabilities into the hands of cybercriminals, terrorists, and other malign actors. The application of AI technologies could also—intentionally or unintentionally—abet bias, discrimination, and other undesirable social outcomes. Technologists warn that the complexity and opacity of AI systems mean there is a meaningful risk that they become configured in a way that is antithetical to human objectives, pursuing their own goals at the expense of human welfare.38

“Technologists warn that the complexity and opacity of AI systems mean there is a meaningful risk that they become configured in a way that is antithetical to human objectives, pursuing their own goals at the expense of human welfare.”

At the same time, the race to achieve transformative AI and harvest its benefits is not only among companies but among countries, particularly the United States and China. The stakes are not only economic but also geopolitical. Leadership in transformative AI offers the promise of economic dynamism, military superiority, and centrality as a global partner to other nations.39

These factors further complicate the trade-offs of various policy approaches to transformative AI. On the one hand, the prospect of misuse and misalignment—along with concerns about economic dislocation and job losses from rapid AI deployment—would appear to favor a “go slow, go carefully” approach to the pursuit and diffusion of transformative AI. On the other hand, the competitive dynamics between the United States and China push toward the desire to “go fast” on both frontier research (particularly if it has strong winnertake- all properties) and deployment (particularly if the fast-follower paradigm predominates) to avoid losing the AI race and allowing a competitor—serving its distinct political interests—to control a powerful technology. The differing regulatory approaches to AI across the European Union, China, and the United States (and even changes within the United States across presidential administrations) both reflect these tensions and will shape the trajectory that transformative AI may follow within the quadrant framework.40

Five Major Policy Implications

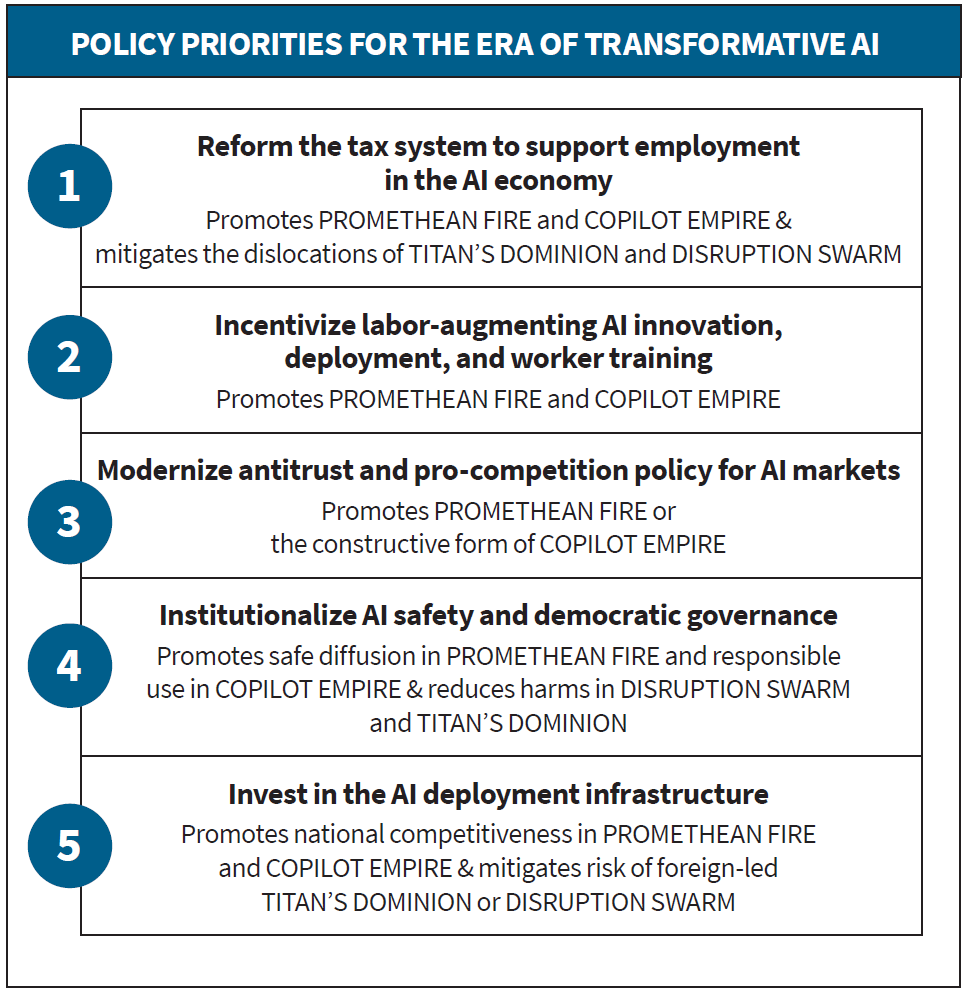

Different quadrants present different principal challenges and underscore different policy priorities: In Titan’s Dominion, the priority is maintaining democratic governance of AI, forestalling exploitative alliances between government and AI corporate interests; in Copilot Empire, it is harnessing the productive power of AI while reining in potential monopolistic abuses; in Disruption Swarm, it is shielding workers from dislocations and maintaining societal cohesion in an era of rapid change; in Promethean Fire, it is leveraging the potential of transformative AI to raise living standards while containing misuse and misalignment.

Policy should therefore prepare to be flexible in anticipation of different quadrant outcomes. It should also incentivize movement toward desirable end states—specifically, the positive versions of the Promethean Fire and Copilot Empire quadrants—while embracing policies that are robust across multiple quadrants. One key principle is to establish policy levers that are designed in advance but which can be tuned and calibrated based on how the AI future is unfolding—levers that are proactive but flexible.41

Priority 1: Reform the tax system to support employment in the AI economy

Promotes Promethean Fire and Copilot Empire & mitigates the dislocations of Titan’s Dominion and Disruption Swarm

The existing tax code contains numerous incentives for capital investment. Profits, dividends, and capital gains face low effective tax rates, supported by an array of provisions like accelerated depreciation and expensing that were further expanded in 2025. Meanwhile, hiring workers is expensive, due not only to income and payroll taxes (the overall labor-tax “wedge”) but also to costly benefits like employer-provided health insurance. Such a system is arguably justified in a world in which capital complements labor, boosting labor productivity that is shared with workers through higher wages. But this system creates perverse incentives and dangerous societal outcomes when it incentivizes large-scale capital investment in AI to replace workers for even small efficiency gains.42

“The prospect of dramatic labor replacement by transformative AI requires consideration of forceful measures that can be deployed to reduce the cost of hiring workers.”

The prospect of dramatic labor replacement by transformative AI requires consideration of forceful measures that can be deployed to reduce the cost of hiring workers. This could include the reduction of Social Security and Medicare payroll taxes at the federal level, paid for by an earmarked stream of revenues from higher taxes on capital. Those higher taxes on capital could be general, better balancing the effective taxation of labor and capital that has shifted markedly in favor of capital in recent decades. Or they could focus on the largest concentrations of super-normal AI-related profits and rents, if winner-take-all dynamics dominate. To address the cost of non-wage benefits, debates on proposals such as the public option for medical insurance should be revived with attention to design details, state-level experiences to date, and versions that allow employer buy-in.43

The advantage of reforming the tax system along these lines is that it—in principle—offers a flexible tool that can be adjusted responsively to the potential paths that AI might take. Should the technology take on a more labor-augmenting character, less adjustment in rates would be needed. In contrast, if AI generates powerful income concentration and labor-replacement dynamics, larger rate adjustments—and larger income supports, including workerside wage subsidies (e.g., expanded earnedincome tax credit or wage insurance) or even non-employment-linked transfers to share the fruits of AI-generated abundance—would be needed to address the distributional consequences and to shape the economics of firm-level capital/labor decisions.44

Priority 2: Incentivize labor-augmenting AI innovation, deployment, and worker training

Promotes Promethean Fire and Copilot Empire

Government also has a critical role to play in shaping AI innovation, directing public R&D funds and procurement at models of AI deployment that raise worker proficiency and productivity. This includes scaling up federal R&D grants for testing innovative human-AI collaboration—building on efforts at the NSF National AI Research Institutes, DARPA, and ARPA-H—and expanding access to compute and data via the National AI Research Resource (NAIRR). It also includes creating a “worker-augmenting AI” track in the Small Business Innovation Research and Technology Transfer (SBIR/STTR) programs to build and test working prototypes and move successful tools into government and commercial use. Finally, government procurement must demand AI solutions that build in-house expertise by empowering public servants with AI copilots (with measurable indicators like outputper- hour, time-to-proficiency, and customer satisfaction) rather than outsourcing capacity through turnkey automation that leads to vendor lock-in, service failure, and cost overruns.45

“In the same way that investments in public education played a vital role in preparing American workers for the transition from an agricultural to industrial economy starting in the late 19th century, the broader US educational system will also need to adapt to current workforce needs and harness AI tools for new approaches to learning.”

Preparing current and future workers for a new era of AI tools is another critical element for achieving a worker-centered AI future. Federal grants to defray the costs of company training programs and collaborative AI adoption recognize that the human capital produced is a public good. Federal programs like the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) can help scale up training models with proven results (e.g., Year Up United, Project QUEST) as well as registered apprenticeships, cultivating partnerships between employers and community colleges that focus on the skills workers need to use AI effectively in the workplace. In the same way that investments in public education played a vital role in preparing American workers for the transition from an agricultural to industrial economy starting in the late 19th century, the broader US educational system will also need to adapt to current workforce needs and harness AI tools for new approaches to learning.46

Civil society also has a role to play in elevating the prestige of human-AI collaboration models, including through competitions, prizes, and widely adopted transparency standards. For example, organizations like the Partnership on AI have developed guidelines for responsible AI practices and job impact assessment tools; these could be further developed into a LEAD/AI (Labor-Enhancing AI Deployment) certification similar to the LEED certification for environmentally friendly buildings, creating a reputational incentive for labor-augmenting AI deployment.47

Priority 3: Modernize antitrust tools and pro-competition policy for AI markets

Promotes Promethean Fire or the constructive form of Copilot Empire

Regulation in the AI era should aim to strike a balance between excessive interference that stifles innovation and excessive restraint that allows abusive practices to proliferate. One approach to this dilemma is a “guardrails and triggers” approach in which the government establishes foundational rules of the road to promote competition, while preparing an advance roadmap of further interventions to be deployed if the evolution of the technology and market structure warrant escalation across the cloud/compute, frontier model, and applications layers.48

Basic guardrails to promote competition among frontier AI companies would include standards-based interoperability requirements, such as well-documented, stable, and nondiscriminatory application programming interfaces (APIs) accessible to third parties. This reduces the frictions involved in switching AI providers and enables customers to avoid being locked in by software infrastructure. Complementary portability rules would fulfill a similar function by requiring AI providers to enable customers to move their AI interaction data between providers in machine-readable formats with privacy, security, and intellectual property protections, without disclosing provider trade secrets or model internals. Prohibitions on exclusivity arrangements or other terms that materially impede customers from engaging with competing AI providers (multihoming) are another element that can be clarified and enforced within existing US antitrust frameworks at the application and distribution layers. Other policies that could be considered for guardrails or potential triggers include infrastructure-level cloud nondiscrimination and switching rules that address egress fees, restrictive licensing, and self-preferencing for affiliated AI businesses. Federal procurement guidance already incorporates many of these principles; competition policy can extend them beyond government buyers.49

It is possible that even with these guardrails, economic forces will push the frontier AI ecosystem toward high concentration or bottleneck control over critical inputs. In that case—and depending on the emerging contours of industry structure and its integration with the rest of the economy– an even more intrusive set of regulatory interventions may be needed to prevent rent extraction and stifled innovation. To prepare for these contingencies, and ensure that sufficient capacity exists within the government to address them, agencies like the Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission should continue to expand their teams focusing on technology and AI competition issues, including those with expertise in cloud economics and AI systems engineering.50

Priority 4: Institutionalize AI safety and democratic governance

Promotes safe diffusion in Promethean Fire and responsible use in Copilot Empire & reduces harms in Disruption Swarm and Titan’s Dominion

The prospect of transformative AI amplifies the consequences of misuse and misalignment in any of the quadrants, making policies to address these risks integral. The “guardrails and triggers” approach is also a useful framework for advancing safety and democratic governance. The prevention of harms from AI is not only important in its own right. Preventing AI accidents is also essential for sustaining societal support for AI diffusion and the realization of its potential benefits.51

“The prevention of harms from AI is not only important in its own right. Preventing AI accidents is also essential for sustaining societal support for AI diffusion and the realization of its potential benefits.”

One key guardrail for AI safety is transparency around the highest-risk development and deployment activities. The Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) should finalize and implement its proposed rule (using authorities in the Defense Production Act) to mandate that frontier AI companies and cloud providers report certain advanced AI training runs and large compute clusters. This would provide policymakers with early line of sight into consequential AI advances. Pre-deployment guardrails for AI models should emphasize arm’s-length, independent evaluations and red-teaming for dangerous capabilities, along with clear documentation and safety mitigations tied to evaluation results, building on the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) AI Risk Management Framework. Post-deployment requirements should include standardized incident logging and time-bound reporting for material safety events at the federal level, building on the system proposed for cyberattacks on critical infrastructure. On the democratic governance side, clear and plain-language disclosure of when and how AI is used in consequential decisions—along with a meaningful human-review backstop and specified appeal mechanisms—should be standard practice for government and encouraged across industry.52

If these requirements fail to prevent abuse, trigger mechanisms should be in place to sanction abusive practices and respond to critical incidents. Regulatory intervention via the Federal Trade Commission is one pathway that has already been used to combat discriminatory facial recognition and deceptive marketing around AI technologies. Mechanisms can be considered for narrowly tailored product-recall-like authorities that would enable the government to order the withdrawal of harmful models or applications, after due process and a high evidentiary bar. Tort law is another key tool: Legislatures and courts should modernize tort standards for AI—with potential safe harbors for adherence to recognized AI risk-management standards—so civil liability deters egregious conduct while preserving room to innovate.53

Priority 5: Invest in the AI deployment infrastructure

Promotes national competitiveness in Promethean Fire and Copilot Empire & mitigates the risk of foreign-led Titan’s Dominion or Disruption Swarm

While there are societal risks to the rapid achievement and diffusion of transformative AI, there are also risks to being slow to adopt AI technologies and being left behind on productivity gains, scientific discoveries, and national security benefits. It will take years to prepare the physical, organizational, and policy infrastructure for AI adoption; investments today help prevent these factors from becoming bottlenecks in the future.

“It will take years to prepare the physical, organizational, and policy infrastructure for AI adoption; investments today help prevent these factors from becoming bottlenecks in the future.”

The most important physical bottlenecks for AI deployment are energy and semiconductors. On the energy side, electricity demands for the training of frontier models and for inference in the application of AI tools will be enormous in the coming years, requiring major investments in power generation, transmission, and distribution with safeguards to avoid shifting higher utility prices onto households and small businesses. The 2025 “America’s AI Action Plan” calls for expedited permitting for data centers and the power they require; agencies and states must now translate that into predictable, timecertain approvals so that projects can execute on schedule. Other priorities include implementation of transmission and interconnection reforms, near-term grid-enhancing technologies that add capacity to existing lines, and demand-side flexibility from large loads (e.g., data centers) to reduce peak strain and accelerate interconnections. On the semiconductor side, developing secure and resilient supply chains is a national and economic security priority. Programs initiated under the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 to bolster onshore fabrication—and build advanced packaging and high-bandwidth memory (HBM) capacity— should be carried through and expanded, paired with partnerships with allies for upstream critical materials and other key parts of the supply chain.54

Investments are also needed in the regulatory, policy, and institutional infrastructure to promote effective diffusion and deployment of AI. This includes modernizing the legal “data plumbing” so that firms can put data to work lawfully and safely across sensitive sectors like health, finance, and education – facilitating usability while protecting privacy through de-identification, purpose-limited sharing, and consumer-permissioned access. It includes time-limited regulatory sandboxes for testing AI applications in regulated industries to accelerate learning while containing risk, as well as development of extension programs similar to NIST’s Manufacturing Extension Partnership to promote diffusion of safe and reliable AI models to small enterprises.55

Conclusion

While it is impossible to anticipate all the implications of transformative AI for the economy and society, it is critical to have a rigorous framework for evaluating the potential trajectories and guiding policy action.56

The framework presented in this essay identifies essential attributes of past technological revolutions, focusing on two axes: winner-take-all versus fast-follower dynamics and labor-replacing versus laboraugmenting effects. This approach surfaces historical analogs relevant to the AI era, offers insight into the potential paths for AI’s integration into the economy, and highlights specific challenges and opportunities for an era of transformative AI.

History shows that competing values are at play in an era of rapid change. We want stability but not stagnation. We want dynamism but not disorder.

Our choices in governments, markets, and civic life will shape whether AI tends toward the promise of Promethean Fire or the peril of Titan’s Dominion, the potential of Copilot Empire or the pain of Disruption Swarm. We have at our disposal practical levers—tax reform, labor-augmenting innovation and training, modernized antitrust, institutionalized safety and democratic governance, and AI deployment infrastructure—to help steer these outcomes.

Past technological revolutions rewarded societies that paired technological with institutional innovation and undertook purposeful adaptation to seize the opportunities and confront the challenges unleashed by frontier invention. With the same determination and sense of purpose, leaders across government, business, and civil society can build the foundations this moment demands and set the course toward a prosperous, broad-based AI future.

“Our choices in governments, markets, and civic life will shape whether AI tends toward the promise of Promethean Fire or the peril of Titan’s Dominion, the potential of Copilot Empire or the pain of Disruption Swarm.”

1. See Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, “Will Humans Go the Way of Horses?” Foreign Affairs (July/August 2015), https://www.philadelphiafed.org/-/media/frbp/assets/events/2015/the-economy/2015-philadelphia-fed-policy-forum/ brynjolfsson-humans-horses.pdf, and Wassily Leontief, “Technological Advance, Economic Growth, and the Distribution of Income,” Population and Development Review 9, no. 3 (September 1983): 403–410, https://doi.org/10.2307/1973315.

2. See Willem van Schendel, A History of Bangladesh (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

3. See Prasannan Parthasarathi, Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600–1850 (Cambridge University Press, 2011) and Katherine Moos, “The Political Economy of State Regulation: The Case of the British Factory Acts,” Cambridge Journal of Economics 45, no. 1 (January 2021): 61–84, https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/beaa034.

4. See Carl Shapiro and Hal Varian, Information Rules: A Strategic Guide to the Network Economy (Harvard Business School Press, 1999).

5. See Constantinos Markides and Paul Geroski, Fast Second: How Smart Companies Bypass Radical Innovation to Enter and Dominate New Markets (Jossey-Bass, 2005) and David J. Teece, “Profiting from Technological Innovation: Implications for Integration, Collaboration, Licensing, and Public Policy,” Research Policy 15, no. 6 (December 1986): 285–305, https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-7333(86)90027-2.

6. For a review of the methods economists have used to model labor-substituting and labor-complementing technological change, see Daniel Susskind, “Technological Unemployment,” in The Oxford Handbook of AI Governance, eds. Justin Bullock et al. (Oxford University Press, 2022).

7. See David Autor, Frank Levy, and Richard Murnane, “The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 18, no. 4 (November 2003): 1279–1333, https://doi.org/10.1162/003355303322552801.

8. See Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, “Automation and New Tasks: How Technology Displaces and Reinstates Labor,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 33, no. 2 (Spring 2019): 3–30, https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.2.3, and David Autor, “Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 29, no. 3 (Summer 2015): 3–30, https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.29.3.3.

9. See David Autor, “Work of the Past, Work of the Future,” Richard T. Ely Lecture, AEA Papers and Proceedings 109 (2019): 1–32, https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20191110, and James Besson, Learning By Doing: The Real Connection Between Innovation, Wages, and Wealth (Yale University Press, 2015).

10. See Timothy Bresnahan and Manuel Trajtenberg, “General Purpose Technologies ‘Engines of Growth’?” Journal of Econometrics 65, no. 1 (January 1995): 83–108, https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(94)01598-T, and Erik Brynjolfsson, Daniel Rock, and Chad Syverson, “The Productivity J-Curve: How Intangibles Complement General Purpose Technologies,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 13, no. 1 (January 2021): 333–372, https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.20180386.

11. See Henry Bennett, Life on the English Manor: A Study of Peasant Conditions, 1150–1400 (Cambridge University Press, 1937) and Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson, Power and Progress: Our 1000-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity (PublicAffairs, 2023).

12. See Sven Beckert, Empire of Cotton: A Global History (Knopf, 2014). For discussion of the role of British imperial policies in the context of other economic and technological factors, see Parthasarathi, Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not, and Indrajit Ray, “Identifying the Woes of the Cotton Textile Industry in Bengal: Tales of the Nineteenth Century,” Economic History Review 62, no. 4 (November 2009): 857–892, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2009.00444.x.

13. See Alfred Chandler, The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business (Harvard University Press, 1977).

14. See Richard B. du Boff, “The Telegraph in Nineteenth-Century America: Technology and Monopoly,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 26, no. 4 (October 1984): 571–586, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417500011178; Dave Donaldson and Richard Hornbeck, “Railroads and American Economic Growth: A ‘Market Access’ Approach,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 131, no. 2 (February 2016): 799–858, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjw002; Elizabeth Granitz and Benjamin Klein, “Monopolization by ‘Raising Rivals’ Costs’: The Standard Oil Case,” Journal of Law and Economics 39, no. 1 (April 1996): 1–47, https://ssrn.com/abstract=1872213; and Richard White, Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America (W.W. Norton, 2011).

15. See Thomas K. McCraw, Prophets of Regulation (Harvard University Press, 1984) and Melvyn Dubofsky, The State and Labor in Modern America (University of North Carolina Press, 1994).

16. See Gerald Brock, The Second Information Revolution (Harvard University Press, 2003) and Tim Wu, The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires (Vintage, 2011).

17. See Autor, “Work of the Past, Work of the Future.”

18. See Robert Allen, “Engels’ Pause: Technical Change, Capital Accumulation, and Inequality in the British Industrial Revolution,” Explorations in Economic History 46, no. 4 (October 2009): 418–435, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2009.04.004.

19. See Carl Benedikt Frey, The Technology Trap: Capital, Labor, and Power in the Age of Automation (Princeton University Press, 2019).

20. See Katherine Moos, “The Political Economy of State Regulation: The Case of the British Factory Acts,” Cambridge Journal of Economics 45, no. 1 (January 2021): 61–84, https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/beaa034; Douglas Irwin and Maksym Chepeliev, “The Economic Consequences of Sir Robert Peel: A Quantitative Assessment of the Repeal of the Corn Laws,” Economic Journal 131, no. 640 (November 2021): 3322–3337, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w28142/w28142.pdf; and Simon Szreter, “Economic Growth, Disruption, Deprivation, Disease, and Death: On the Importance of the Politics of Public Health for Development,” Population and Development Review 23, no. 4 (December 1997): 693–728, https://doi.org/10.2307/2137377.

21. See Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, “Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets,” Journal of Political Economy 128, no. 6 (2020): https://shapingwork.mit.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Robots-and-Jobs-Evidence-from-US-Labor-Markets.p.pdf; David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson, “Untangling Trade and Technology: Evidence from Local Labour Markets,” Economic Journal 125 (May 2015): 621–646, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12245; and Anne Case and Angus Deaton, “Mortality and Morbidity in the 21st Century,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (Spring 2017): 397–476, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/casetextsp17bpea.pdf.

22. See Robert Gordon, The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War (Princeton University Press, 2016).

23. See Paul David, “The Dynamo and the Computer: An Historical Perspective on the Modern Productivity Paradox,” American Economic Review 80, no. 2 (January 1990): 355–361, in Papers and Proceedings of the 102nd Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association (May 1990), https://www.jstor.org/stable/2006600; and Robert Gordon, The Rise and Fall of American Growth.

24. See James Bessen, “Automation and Jobs: When Technology Boosts Employment,” Economic Policy 34, no. 100 (October 2019): 589–626, https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship/815/.

25. See John Rae, The American Automobile Industry (GK Hall and Company, 1984).

26. See Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz, The Race Between Education and Technology (Harvard University Press, 2008) and John Fernald, “Roads to Prosperity? Assessing the Link Between Public Capital and Productivity,” American Economic Review 89, no. 3 (June 1999): 619–638, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.89.3.6193.

27. See Anton Korinek and Jai Vipra, “Concentrating Intelligence: Scaling and Market Structure in Artificial Intelligence,” Economic Policy 40, no. 121 (January 2025): 225–256, https://www.ineteconomics.org/uploads/papers/WP_228-Korinek-and-Vipra.pdf, and Jon Schmid, Tobias Sytsma, and Anton Shenk, Evaluating Natural Monopoly Conditions in the AI Foundation Model Market (RAND Corporation, 2024), https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA3400/RRA3415-1/RAND_RRA3415-1.pdf.

28. See Financial Times, “Inside the Relentless Race for AI Capacity,” July 30, 2025, https://ig.ft.com/ai-data-centres/; LMSYS Org, “Chatbot Arena Leaderboard,” https://lmarena.ai/leaderboard; Stanford Center for Research on Foundation Models, “HELM Capabilities,” https://crfm.stanford.edu/helm/capabilities/latest/; and Will Knight, “DeepSeek’s New AI Model Sparks Shock, Awe, and Questions from US Competitors,” Wired, January 28, 2025, https://www.wired.com/story/deepseek-executives-reaction-silicon-valley/.

29. For persistence of scaling laws and computational requirements, see Jensen Huang, “GTC March 2025 Keynote with NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang – From One to Three Scaling Laws,” at 11:00, YouTube, March 18, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/live/_waPvOwL9Z8?si=55eLeOxOLYmw-dE3.

30. See The Economist, “Faith in God-like Large Language Models is Waning,” September 8, 2025, https://www.economist.com/business/2025/09/08/faith-in-god-like-large-language-models-is-waning. For the falling cost of inference, see AI Index Steering Committee, Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2025 (Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, 2025), https://hai.stanford.edu/ai-index/2025-ai-index-report.

31. See Erik Brynjolfsson, “The Turing Trap: The Promise and Peril of Human-Like AI,” Daedulus 151, no. 2 (Spring 2022): 272–287, https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_01915; Daniel Susskind, A World Without Work: Technology, Automation, and How to Respond (Allen Lane, 2020); and Thibault Spirlet, “The CEO of Anthropic is Doubling Down on His Warning that AI Will Gut Entry-Level Jobs,” Business Insider, September 5, 2025, https://www.businessinsider.com/anthropic-ceo-ai-cut-entry-level-law-finance-consulting-jobs-2025-9.

32. See Erik Brynjolfsson, Bharat Chandar, and Ruyu Chen, “Canaries in the Coal Mine? Six Facts about the Recent Employment Effects of Artificial Intelligence,” Working Paper, Stanford Digital Economy Lab, August 26, 2025, https://digitaleconomy.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Canaries_BrynjolfssonChandarChen.pdf, and Derek Thompson, “Something Alarming is Happening to the Job Market,” The Atlantic, April 30, 2025, https://www.theatlantic.com/economy/archive/2025/04/job-market-youth/682641/. For alternative views, see Sarah Eckhardt and Nathan Goldschlag, “AI and Jobs: The Final Word (Until the Next One),” Economic Innovation Group, August 10, 2025, https://eig.org/ai-and-jobs-the-final-word/, and Noah Smith, “Stop Pretending You Know What AI Does to the Economy,” Noahpinion, Substack, July 20, 2025, https://www.noahpinion.blog/p/stop-pretending-you-know-what-ai.

33. See Erik Brynjolfsson, Danielle Li, and Lindsey Raymond, “Generative AI at Work,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 140, no. 2 (May 2025): 889–942, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjae044; Sida Peng et al., “The Impact of AI on Developer Productivity: Evidence from GitHub Copilot,” preprint, arXiv, February 13, 2023, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.06590; Leonardo Gambacorta et al., “Generative AI and Labour Productivity: A Field Experiment on Coding,” Working Paper No. 1208 (BIS, September 2024), https://www.bis.org/publ/work1208.pdf; Shakked Noy and Whitney Zhang, “Experimental Evidence on the Productivity Effects of Generative Artificial Intelligence,” Science 381, no. 6654 (2023): 187-192, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adh2586; Jonathan Choi, Amy Monahan, and Daniel Schwarcz, “Lawyering in the Age of Artificial Intelligence,” Minnesota Law Review 109, no. 1 (2024): 147–217, https://minnesotalawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/3-ChoiMonahanSchwarcz.pdf; Jung Ho Choi and Chloe Xie, “Human + AI in Accounting: Early Evidence from the Field,” Stanford University Graduate School of Business Research Paper No. 4261, MIT Sloan Research Paper No. 7280-25, May 2025, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.06590; and Nicholas Otis et al., “The Uneven Impact of Generative AI on Entrepreneurial Performance,” Working Paper 24-042 (Harvard Business School, December 2023), https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%20Files/24-042_9ebd2f26-e292-404c-b858-3e883f0e11c0.pdf.

34. See Isabella Loaiza and Roberto Rigobon, “The EPOCH of AI: Human-Machine Complementarities at Work,” Research Paper No. 7236-24 (MIT Sloan, 2024), http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5028371.

35. See Yijia Shao et al., “Future of Work with AI Agents: Auditing Automation and Augmentation Potential Across the U.S. Workforce,” preprint, arXiv, June 2025, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2506.06576; Fabrizio Dell’Acqua et al., “Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier: Field Experimental Evidence on the Effects of AI on Knowledge Worker Productivity and Quality,” Working Paper 24-013 (Harvard Business School, September 22, 2023), https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%2520Files/24-013_d9b45b68-9e74-42d6-a1c6-c72fb70c782.pdf; Fabrizio Dell’Acqua et al., “The Cybernetic Teammate: A Field Experiment on Generative AI Reshaping Teamwork and Expertise,” Working Paper 25-043 (Harvard Business School, March 28, 2025), https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=67197; and Sendhil Mullainathan, “Economics in the Age of Algorithms,” AEA Papers and Proceedings 115 (2025): 1–23, https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20251118.

36. See Bresnahan and Trajtenberg, “General Purpose Technologies ‘Engines of Growth’?” and Brynjolfsson, Rock, and Syverson, “The Productivity J-Curve: How Intangibles Complement General Purpose Technologies.” 37. See Hal Varian, “Automation Versus Procreation (a.k.a., Bots Versus Tots),” VOXEU Column, March 30, 2020, https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/automation-versus-procreation-aka-bots-versus-tots.

38. See Yoshua Bengio et al., International AI Safety Report 2025 (UK Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, January 2025), https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2501.17805, and Dan Hendrycks, Mantas Mazeika, and Thomas Woodside, “An Overview of Catastrophic AI Risks,” Center for AI Safety, preprint, arXiv, October 9, 2023, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2306.12001. 39. See Eric Schmidt et al., National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence Final Report, 2021, https://assets.foleon.com/eu-central-1/de-uploads-7e3kk3/48187/nscai_full_report_digital.04d6b124173c.pdf, and James Black et al., “Strategic Competition in the Age of AI: Emerging Risks and Opportunities from Military Use of Artificial Intelligence” (RAND Europe, September 2024), https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA3295-1.html.

40. See Gregory Allen, DeepSeek, Huawei, Export Controls, and the Future of the U.S.- China AI Race (Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 2025), https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep68307; Kyle Chan et al., “Full Stack China’s Evolving Industrial Policy for AI,” RAND, June 29, 2025, https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PEA4012-1.html; and Kai-Fu Lee, AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order (Houghton Mifflin, 2018).

41. In theory, if governments were able to solve the “distribution problem” (i.e., a mechanism for distributing broadly the economic benefits of transformative AI automation across the population, so that those displaced by mass unemployment would enjoy higher living standards), then one could argue that a future world without human work is actually desirable and that we should embrace a labor-replacing AI future. The history of previous technological revolutions, however, suggests that this is not the way that the nexus between economic resources and political power plays out in actual human experience. It is therefore preferable from a political economy and social stability perspective for policy to push the system in the direction of the labor-augmenting quadrants.

42. See Fernanda Brollo et al., “Broadening the Gains from Generative AI: The Role of Fiscal Policies,” Staff Discussion Note, International Monetary Fund, June 2024, https://doi.org/10.5089/9798400277177.006; OECD, Taxing Wages 2025: The United States (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2025), https:// www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/topics/policy-issues/tax-policy/taxingwages- brochure.pdf; and Amy Finkelstein et al., “The Health Wedge and Labor Market Inequality,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (Spring 2023): 425–475, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/16653-BPEA-SP23_WEB_Finkelstein-et-al_session_print.pdf.

43. See Daron Acemoglu, Andrea Manera, and Pascual Restrepo, “Taxes, Automation, and the Future of Labor,” Research Brief, MIT Future of Work, September 29, 2020, https://mitsloan.mit.edu/shared/ods/documents?PublicationDocumentID=7929; Anton Korinek, “Taxation and the Vanishing Labor Market in the Age of AI,” The Ohio State Technology Law Journal 16, no. 1 (2020): 245–257, https://kb.osu.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/d0b0ea57-4c8b-46cd-8c25-a69f3050b38b/content; and John Holahan, Michael Simpson, and Linda Blumberg, “What Are the Effects of Alternative Public Option Proposals,” Urban Institute Research Report, March 17, 2021, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/what-are-effects-alternative-publicoption-proposals. 44. See Anton Korinek and Megan Juelfs, “Preparing for the (Non-Existent?) Future of Work,” Working Paper No. 3 (Brookings Center of Regulation and Markets, August 2022), https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/2022.08.10_Korinek-Juelfs-Final.pdf; Benjamin Hyman, Brian Kovak, and Adam Leive, “Wage Insurance for Displaced Workers,” Staff Report No. 1105, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, May 2024, https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/staff_reports/sr1105.pdf; and Jacob Bastian, “Do Wage Subsidies Increase Labor Force Participation? Evidence from Around the World,” Brookings Institution, May 23, 2025, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/do-wage-subsidies-increase-labor-force-participation/.

45. See Daron Acemoglu, David Autor, and Simon Johnson, “Can We Have Pro- Worker AI? Choosing a Path of Machines in Service of Minds,” Policy Memo, MIT Shaping the Future of Work, September 19, 2023, https://shapingwork.mit.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Pro-Worker-AI-Policy-Memo.pdf; Rayid Ghani et al., Strategies for Integrating AI into State and Local Government Decision Making (The National Academies Press, 2025), https://doi.org/10.17226/29152; Christopher Barlow et al., Enhancing Acquisition Outcomes Through Leveraging of Artificial Intelligence (MITRE Corporation, 2025), https://www.mitre.org/sites/default/files/2025-03/PR-24-0962-Leveraging-AI-Acquisition.pdf.

46. See Erik Brynjolfsson et al., Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work (The National Academies Press, 2025), https://doi.org/10.17226/27644; Matthias Oschinski, Ali Crawford, and Maggie Wu, “AI and the Future of Workforce Training,” Issue Brief, Center for Security and Emerging Technology, December 2024, https://cset.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/CSET-AI-and-the-Future-of-Workforce- Training.pdf; U.S. Department of Education, Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Teaching and Learning: Insights and Recommendations (DOE Office of Educational Technology, 2023), https://www.ed.gov/sites/ed/files/documents/ai-report/ai-report.pdf.

47. See Partnership on AI, “Guidelines for AI and Shared Prosperity,” June 7, 2023, https://partnershiponai.org/paper/shared-prosperity/.

48. The “guardrails and triggers” approach complements the 2023 DOJ/FTC Merger Guidelines by addressing a similar set of foreclosure risks ex ante, not only at merger time. See U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission, “Merger Guidelines,” December 18, 2023, https://www.justice.gov/d9/2023-12/2023%20Merger%20Guidelines.pdf.

49. See Ganesh Sitaraman and Tejas Narechania, “An Antimonopoly Approach to Governing Artificial Intelligence,” Yale Law and Policy Review 43, no. 5 (2024): 95–170, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4597080; Jack Corrigan, “Promoting AI Innovation Through Competition: A Guide to Managing Market Power,” Issue Brief, Center for Security and Emerging Technology, May 2025, https://doi.org/10.51593/20230052; and Office of Management and Budget, “Driving Efficient Acquisition of Artificial Intelligence,” Memorandum M-25-22, April 3, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/M-25-22-Driving-Efficient-Acquisition-of-Artificial-Intelligence-in-Government.pdf.

50. See UK Competition and Markets Authority, “AI Foundation Models: Update Paper,” April 11, 2024, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/661941a6c1d297c6ad1dfeed/Update_Paper__1_.pdf.

51. See Bengio et al., International AI Safety Report 2025.

52. See Department of Commerce Bureau of Industry and Security, “Establishment of Reporting Requirements for the Development of Advanced Artificial Intelligence Models and Computing Clusters,” 15 CFR 702, 89 Fed. Reg. 176 (September 11, 2024), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/09/11/2024-20529/establishment-of-reporting-requirements-for-the-development-of-advanced-artificial-intelligence; Shayne Longpre et al., “Position: A Safe Harbor for AI Evaluation and Red Teaming,” Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning 235 (2024): 32691-32710, https://proceedings.mlr.press/v235/longpre24a.html; Lindsey Gailmard, Drew Spence, and Daniel Ho, “Adverse Event Reporting for AI: Developing the Information Infrastructure Government Needs to Learn and Act,” Issue Brief, Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, July 2025, https://hai.stanford.edu/assets/files/hai-reglab-issue-brief-adverse-eventreporting-for-ai.pdf.

53. See Christina Lee, “Beyond Algorithmic Disgorgement: Remedying Algorithmic Harms,” Public Law Research Paper 2025–26 (George Washington Law School, 2025), http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5212510, and Gregory Smith et al., “Liability for Harms from AI Systems,” RAND Research, November 20, 2024, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA3243-4.html.

54. See The White House, “Winning the Race: America’s AI Action Plan,” July 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Americas-AIAction-Plan.pdf; Cy McGeady et al., The Electricity Supply Bottleneck on U.S. AI Dominance (Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 2025), https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2025-03/250303_McGeady_Electricity_Bottleneck.pdf; Will Chueh and Karen Skelton, “Meeting 21st Century U.S. Electricity Demand: Readout from Stanford Dialogue,” Stanford Precourt Institute for Energy and Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability, April 2025, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1akisKBhJSbwkcJ8jM_KsHN1CeadaH06S/view; and U.S. Department of Commerce, “The CHIPS Program Office Vision for Success: Two Years Later,” CHIPS for America, National Institute of Standards and Technology, January 2025, https://www.nist.gov/system/files/documents/2025/01/10/The%20CHIPS%20Program%20Office%20Vision%20for%20Success%20-%20Two%20Years%20Later.pdf.

55. See Gillian Diebold, Overcoming Barriers to Data Sharing in the United States (Center for Data Innovation, September 25, 2023), https://www2.datainnovation.org/2023-data-sharing-barriers.pdf; OECD/BCG/INSEAD, The Adoption of Artificial Intelligence in Firms: New Evidence for Policymaking (OECD Publishing, 2025), https://doi.org/10.1787/f9ef33c3-en; and OECD, “Regulatory Sandboxes in Artificial Intelligence,” OECD Digital Economy Papers No. 356, July 2023, https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2023/07/regulatory-sandboxes-in-artificial-intelligence_a44aae4f/8f80a0e6-en.pdf.

56. For additional perspective on the potential implications of transformative AI, see Erik Brynjolfsson, Anton Korinek, and Ajay K. Agrawal, “A Research Agenda for the Economics of Transformative AI,” Working Paper No. 34256 (National Bureau of Economic Research, September 2025), https://doi.org/10.3386/w34256, and Anton Korinek, “Economic Policy Challenges for the Age of AI,” Working Paper No. 32980 (National Bureau of Economic Research, September 2024), https://doi.org/10.3386/w32980.